September - October 2016

Dear Friends,

We’ve had a great start to the Fall with our 2017-18 fellowship application process underway and our 2016 Annual Gala! On October 24th, we honored Dwight Anderson and Leymah Gbowee at our Annual Gala. It was an incredible and inspiring night. Thank you to everyone who attended and for your continued support. For more information about our Gala, check out our website! We will sharing photos from the evening soon.

In addition, all of our 2016-17 Fellows are settled into their fellowship posts! This Fellows Flyer is the first edition including the current fellowship class. We are excited to share their experience with you all!

In celebration of our Fellows, we recently had a PiAf Alumni Week. The week consisted of events across the globe, from San Francisco to Cape Town, where PiAf Alumni could catch up and network. We are so proud of our current and past Fellows, which together create a network of over 500 young leaders. We are looking forward to selecting the next fellowship class during this application season!

We hope you enjoy this edition of the Fellows Flyer!

Warm regards,

Jodianna Ringel

Executive Director

PiAf Connections

Please click below to check out pictures of our Fellows, Alums and other members of the PiAf family meeting up at home and around Africa.

Notes from the Field

By Alex Dobyan, 2016-2017 Fellow with African School of Economics in Benin

Alex gets friendly with reptiles while traveling in Ouidah, Benin.

What makes a university a university? I’ve been constantly asking myself that question since arriving at the African School of Economics in Benin last month.

Is it the campus? ASE’s campus is under construction, so classrooms and administrative offices are located in a rented space in two office buildings. Is it the library? ASE has a library, but it consists of a room about as large as my bedroom with bookshelves that are only half-filled. Is it the unlimited freshman meal plans, countless hours logged on JSTOR, and red solo cups that characterized my time as an undergrad at Tufts? Assuredly not – that’s not what the ASE admissions brochures mean when they tout ASE as one of the few Beninese universities created in the “North American” model.

All institutions would be nothing without the people who run them, and so it is at ASE. The professors here are just like professors anywhere – lively, quirky, occasionally scatterbrained, and very dedicated to thinking about and solving the problems of their respective fields. A staff that barely numbers in the double-digits manages to admit students, keep financial records, set up IT systems, and run the operations that keep everything going. And ASE’s grad students are well, students – at times throwing themselves into research and learning about a subject they are passionate about, at times getting distracted on their laptops in class, but mostly stressing out about homework, grades, and finding a job when they graduate.

Still, the task of establishing an institution with a high academic reputation presents challenges that are hard to fathom in America. The cost of an ASE education is about $2300 with financial aid, which is more than double the per capita GDP of Benin. That doesn’t cover meals, or room and board. Books in English are hard to come by in Benin (a Francophone country), and prohibitively expensive. Many students have never had any sustained interactions in English and some have hardly practiced at all since high school, so there’s a steep learning curve to pursuing graduate studies in English. And a number of the students at ASE are pursuing graduate studies in part because the job market simply doesn’t have enough well-paying jobs to absorb all of Benin’s university graduates.

If there’s one commonality between the education the students receive here and what I got at Tufts (and hopefully will get in grad school), it’s that we learn the most outside the classroom. Our peers are the best teachers – the lessons gained from the talented and motivated people around us are worth just as much as any textbook. Many of the students will say that the best part of coming to ASE has been getting to know other students from across the continent and being able to take advantage of the range of experiences of the student body. Now that I’ve become colleagues and friends with a number of the students and faculty here, I would have to agree on that point, and I’m looking forward to what else I will learn over the next year.

Notes from the Field

By Aly Passanante, 2016-2017 Fellow with The Kasiisi Project in Uganda

The Kasiisi Primary School girls’ soccer team.

Mwije tugende kuzaana omupiira! (Come and we go play soccer!)

Girls in rural Uganda typically do not get the chance to play soccer in schools, and often are redirected to play volleyball instead. This year many of the schools that The Kasiisi Project works with have girls’ soccer teams for the first time, and I have the immense privilege of coaching the Kasiisi Primary School girls’ soccer team! The team was started by a summer intern about five weeks before I arrived and while some girls have played before, this is many of the girls’ first experience playing. With that being said, the girls are incredibly eager to learn and love playing! (After an hour and a half practice they always beg me to let them play longer or to borrow soccer balls over the weekend.)

We work on ball skills, positioning, and rules of the game, just like any other team. But ultimately our goal is for these girls to take up positive space at the school and believe that they are just as capable of playing soccer as their male counterparts. On Mondays and Thursdays, the girls have the field, which, given that the field is the communal play space at the school, often leads to boys and the rest of the girls surrounding the field and watching them play. While it’s hard to measure any lasting effects in such a short time period, the girls are already working their way into the boys’ games during lunch break and have offered to show up for practice even during their breaks from school. Our team is a minuscule piece of a much larger puzzle, but we hope to slowly break down gender norms in our community and empower girls to take up more space in other aspects of their lives as well. I’m very excited to witness this progress in our region and also to play a small part in the pilot program!

Notes from the Field

By Christina Amutah, 2016-2017 Fellow with Baylor International Pediatric AIDS Initiative in Botswana

A huge part of moving to a new city is meeting tons of new people. This also means answering the ever stressful question “Where are you from?” Lately, I have found myself alternating between these options

- “I’m American but born in Nigeria”

- “I’m Nigerian but raised in the States”

- “I’m American”

- “I’m Nigerian”

Empirically, all of these statements are true but have different connotations. Mentioning America satisfies questions about my accent, but inspires additional questions like “Where are you really from?” because apparently “American” has a look that doesn’t include me. With Batswana, mentioning Nigeria is sure to draw jokes about Nollywood. If I say nothing, my race invites most people to assume that I am a local. While this is nice for the purposes of blending in on public transport and at malls, it creates some awkward interactions. Once upon meeting me, an American said to me “Your English is so good!” I guess he assumed I was Motswana and also (incorrectly) assumed that an American accent is synonymous with “good English”.

More importantly than these social interactions, how I identify myself and how other people categorize me influences my work. Leading with my Nigerian side allows me to bond over Burna Boy and Davido songs with my teens. Being “African-American” invites them to ask me about hip hop or how I get my hair done. However, just being American invites a variety of assumptions about how much money I have (must be a lot) and how much I like being in Botswana (must not like it that much). All of this impacts how relatable I seem and how my messages are received.

As someone who rarely considers themselves privileged, it has been jarring to be placed in a situation where I have such a significant amount of it. I imagine many other fellows from a variety of backgrounds have been wrestling with this shift as well. Of course things like my race, color, nationality, gender identity, and sexual orientation complicate this idea. Nevertheless, the fact that I traveled halfway across the world by choice (unlike millions who are forced to migrate) is in and of itself a remarkable thing.

I have already learned that perceptions of my privilege are variable but never erasable regardless of which parts of myself I choose to emphasize and deemphasize. Thus, now saddled with it, I feel a responsibility to use it thoughtfully. Sometimes, this could mean signal boosting those around me who may not have as much of a platform. Other times, this can mean doing some simple capacity building by showing a coworker how to do something, instead of doing it for them.

Navigating my identity and my privilege is something that I am still figuring out each and every day. While challenging, I appreciate the opportunity to examine these themes early in my career, as I am sure they will continue to be at play for the remainder of it.

Notes from the Field

By Gracie Rosenbach, 2016-2017 Fellow with Olam International in Uganda

The view of Mt. Elgon from Gracie’s hotel in Mbale.

I applied to be a Princeton in Africa Fellow in part because I wanted to gain “field experience”. In my two months with Olam International, I was surprised to learn that “the field” is one of the most subjective phrases in development.

Working for development organizations in DC, “the field” is anywhere in a developing country, so in order to work in the field, I accepted my fellowship and started my new job in Kampala. However, sitting at a desk all day in an air conditioned office is not considered “the field” to my co-workers. And so, I embarked on my first work trip to visit our farmers in the Mt. Elgon Region, and I stayed just outside in a town called Mbale. “Surely this is the field,” I thought to myself from my nice hotel room. I was quickly proven wrong the next morning, when my driver, Suleiman, and I were ready to begin our day, and he asked, “so are you ready to go to the field?”

Finally, after our hour-long drive on the “road” (read: dirt and rocks that I was sure would destroy our car) up Mt. Elgon and to the village of Budadiri, there was no doubt that I had finally made it to “the field”. After this illustrious quest, I have learned some of the benefits of each level of “the field” and why I am glad to have been able to experience them all.

Kampala (the capital city)

Living in “the field” in Kampala has given me significant insight into a new culture, and allowed me to comfortably ease in to my novel surroundings. The ability to go to the movies, eat at nice restaurants, and do yoga quickly breaks down significant misconceptions and stereotypes that many people hold about Africa, and is a great way to meet new people – Ugandans and expats alike.Mbale (moderate-sized town)

Staying in “the field” in Mbale helped me to experience how a significant amount of Ugandans and Africans live. These moderately-sized towns are developing throughout the continent, and are an interesting intersection between the capital cities where anything is accessible, and the rural villages.Budadiri (coffee-growing village)

Visiting the coffee farmers that Olam works with in “the field” has been one of the best parts of my job so far. I had heard that Ugandans are incredibly welcoming people, however I was overwhelmed by their generosity and kindness when a foreigner unexpectedly showed up at their house to ask them about their farming practices.Now, as I sit in my office in Kampala working on sustainability projects, being able to recall the farmers who I met and thinking about how the projects can benefit them makes my work all the more valuable.

Notes from the Field

By Joseph Schmidt, 2016-2017 Fellow with Maru-a-Pula in Botswana

The front entrance of Maru-a-Pula.

“To teach is to learn twice” – Joseph Joubert

I find that quote to be quite the understatement. Teaching seems to entail learning many things as many times as you plan to teach them. As a teacher in the States, I had to relearn all my curriculum so I could effectively teach it to people who were developing under very different circumstances than me. I had impoverished students of color in the most segregated city in the country walking into my classroom every day. I was just a young white man who loved science. Things didn’t get off swimmingly at first. I had to realize that a teacher has to take cues from his students far more often than the assigned curriculum. Science is about using evidence to explain the phenomena of the world, but one has to realize that phenomena appear differently to different people. After three years I decided to jump into a new setting, to see if I could transfer these skills into a more foreign environment. And so within 48 hours, I cleaned up my classroom, hopped on a plane, and arrived in Gaborone.

Teaching at Maru-a-Pula is a vastly different experience than teaching in inner-city Milwaukee, so once again, it was time to take Mr. Joubert’s advice and relearn science through the eyes of my diverse students. This is an enjoyable task even amid roaring jetlag and the awkwardness of navigating a rather large institution. What kept me on my toes were the students I saw every day. They brought an insatiable sense of curiosity to each class, with some students extending their arms as high as possible waiting for the sweet relief of having a burning question lifted from their heads. Most of my students are from Botswana, while the rest represent nearly 30 other nations. Some students come from significant privilege, while others are present entirely on scholarship.

After being thrown into the classroom in the middle of a term, painstakingly learning very novel names, getting my weekly schedule down pact, and coming to grips with the term’s curriculum, I like to think that I’ve made great progress with the last two months. My students and I have developed a substantial rapport, we make sure to keep each other on our toes, and we ask questions of each other constantly. I’ve begun to find my place within the science department, creating assessments and participating in the development of the curriculum. I’ve become comfortable with the beautiful city I live in. I look forward to starting next term strongly with me in the driver’s seat from the first moment. I will be teaching the same students but expanding my extracurricular presence. I plan to relearn many things many more times, and a couple things (like cricket) for the first of many times, for that is the true work of a teacher.

Notes from the Field

By Rohita Javangula, 2016-2017 Fellow with Global Shea Alliance in Ghana

Rohita talks about what makes shea so unique

When you think of shea you probably think of lotion, but 90% of shea is consumed in food products. Working at the Global Shea Alliance has taught me how unique shea actually is. For one, it only grows in the Sahel region of sub-Saharan Africa and nowhere else in the world. Locally, most people turn the shea kernels into shea oil and use it for cooking. The shea fruit is also edible. I tasted shea fruit for the first time recently and it is delicious! It has a grainy texture but tastes like brown sugar. The fruit itself look like small mangoes and inside is a kernel that looks like a peach pit. The kernels are processed to extract vegetable oil, known as “shea butter”.

Approximately 16 million women collect and process shea as a source of food and income in Africa and shea sales account for 12% of income for poor rural families.

Aside from its edible forms, shea is really good for your skin and hair. While there isn’t a lot of public scientific research on the benefits of shea butter, we have found that shea butter in cosmetics provides a base emollient rich in natural fatty acids and a range of benefits including anti-inflammation and UV protection from its unique unsaponifiable content.

Most recently, I received the opportunity to travel to northern Ghana and visit some women’s cooperatives. As part of GSA’s sustainability program, these women received shea quality improvement trainings where they were taught effective ways to boil, dry, and process shea kernels. There were over 6000 women trained in Ghana alone! One women’s group leader I spoke to said she was incredibly excited that there was a growing interest in shea and all the women in the group look forward to seeing more people buy shea. So, the next time you’re in a grocery store buy some shea products!

Notes from the Field

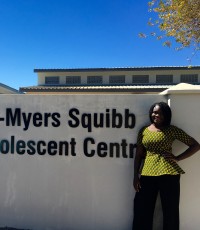

By Vanessa Nyarko, 2016-2017 Fellow with African Leadership Academy in South Africa

Vanessa and two ALA fellows during one of the new hire orientations.

It’s been two years since I’ve been back on the continent of Africa, one month since I’ve been back in the States and four years since my last major orientation.

There’s a Ghanaian word that tends to be overused by tourists and academics that I never fully understood. “Akwaba,” it means welcome. There’s a giant banner that greets you when you land at Kotoka International Airport, which I always used to ignore when I landed because I thought it was for tourists. I walked past the stores selling shorts and bags with the Ghanaian woman holding the pot with “Akwaba” smacked on the bottom of her picture. I have never used this word in any context, but I always heard it, typically never from Ghanaians. I assume the reason I never used it was because I always felt welcome in Ghana and, by any substitute, Ghanaian communities I encountered. It was synonymous with Ghana to me. My grandmother didn’t need to say it when I came to her house, I just felt it.

As a result, when I first landed at O.R Tambo, I was extremely nervous. I’d been to the continent before but never any region outside of West Africa. Besides watching the South African musical Sarafina and taking some South African history classes in college my interaction with South Africa was superficial at best.

However, when I got to the customs and he looked at my passport and asked me about famous Ghanaian soccer players I began to laugh. What was there to be nervous about? Akwaba wasn’t synonymous with Ghana; it was something every country on the continent has. I was being a regional snob, I could find a warm and welcoming community anywhere on the continent including in Honeydew, Johannesburg at the Africa Leadership Academy.

I spent my first month not struggling to fit in or acclimate, but exhausted from new hire induction, all staff retreats and fellows retreats. There was never a time when I was alone, unless I sought it out myself. We explored neighborhoods in Johannesburg, spent time at a game reserve, participated in a serious scavenger hunt and did countless other activities. I spent a whole month being orientated to not only ALA but the continent. I work with Americans, Nigerians, Zimbabweans, South Africans and Ethiopians. Learning their stories and history is better than any class I could have taken. Interacting with them has proved to me that I could really visit any African country and be welcomed with hospitality, curiosity and love.

In my previous life, I was an Orientation Leader at the University of Minnesota and I thought I knew all about orientation and the act of orientating, but I was wrong. After several weeks of orientation of ALA, I can say with confidence, I wouldn’t have met my friends and formed such strong bonds with them without it. I wouldn’t have learned my organization’s mission and values, which strongly influence my work and I wouldn’t have met a series of ALA’s previous Princeton in Africa Fellows (now employees in the ALA network) who showed me how a welcoming environment could make a difference.

Notes from the Field

By Victoria Leonard, 2016-2017 Fellow with Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation in Tanzania

Victoria photographing the drama and dance group’s performance for a story on CCBRT’s advocacy outreach.

Before leaving home it became clear that some family and friends were concerned about my survival. “How will you get around? Will you be able to eat healthily? Where will you sleep?” they asked. “Public transportation, yes, and in a bed” I replied, slightly exasperated at the pervasiveness of assumptions grounded in the “mud hut Africa” stereotype.

I have been privileged to spend time in Senegal, Ghana, and South Africa where that myth has repeatedly been dispelled, even though I worked in primarily rural settings where people actually did live in mud huts, and access to meal options and my preferred shampoo were very slim.

Unknowingly, I carried expectations based on those contexts with me on the plane to Dar. When I arrived, I found myself strangely disappointed by how “easy” I thought my life would be. There are four fully stocked supermarkets close by. Most roads are paved. I live in a seaside apartment with a laundry machine and pool.

However, I assumed wrong. Despite these luxuries, life here is not a walk in the park. In fact, walking itself is luxury. Due to safety concerns, I chart out my daily movements, am skeptical of kind offers, and heed the repeated warnings to never carry a bag. This requisite heightened defensiveness spawned an underlying tension that is far from the chill atmosphere I was used to in the less metropolitan settings where I had worked.

I wasn’t aware of how this tension was steadily shaping my experience of Dar and the people who live here until one month into my fellowship when I reached for my phone and it was nowhere to be found. After retracing my path home and calling it several times, I accepted it was gone.

Why was I willing to give up so easily? Because I assumed that either the bajaji driver had taken my phone, or someone picked it up on the roadside. Why didn’t I expect them to return it? Because I assumed that people walking around would likely be in an economic situation in which they needed a phone themselves or they needed money and could get it by selling the phone. In short, after briefly considering how poverty might affect decision-making, I expected the worst.

Before completely throwing in the towel, I called one last time. Cheche, the bajaji driver who brought me to work that morning, picked up and said he would come right away to return it. Yet again, my assumptions, though seemingly well-intentioned and researched, were wrong.

Now Cheche drives me to work every day at a fair price. He looks out for me and makes sure I’m safe before he drives away. He’s also my friend.

Viewing my transition to Dar in hindsight, it’s clear that when I assume, I’m usually wrong. Having spent time in several African countries does not preclude me from the unreliability, and ultimately the harm, of unquestioned assumptions.

And so it seems the old adage is true.

Notes from the Field

Alumni Update: #PiAfAlumniWeek

Former Fellows and the PiAf Staff at the New York City Happy Hour on September 21st, 2016.

The second-annual PiAf Alumni Week was a huge success! During the week of September 19th, nearly 70 alumni gathered in nine cities around the globe for dinner, drinks, ice cream, and, in D.C., a picnic.

“It is always great to re-connect with the Princeton in Africa family and see new generations of leaders exploring their first career steps,” said Jane Yang, a 2011-2012 Fellow at the International Rescue Committee in Nairobi. Yang was one of nine alumni who had dinner at Habehsa, an Ethiopian restaurant in Nairobi. A big thanks to all of the organizers and to everyone who participated. Stayed tuned for information on upcoming opportunities to continue connecting with fellow alumni!