November - December 2013

Dear Friends,

We have a great Fellows Flyer to share with you! As this issue demonstrates, our Fellows are hard at work across the continent – training cashew farmers in the best practices for farm sanitation and maintenance in Ghana, tracking down elephants in Kenya, interpreting survey data for high school Equalizers in South Africa, and so much more. They are also learning to navigate new cultural and professional environments – and learning about themselves and what they are capable of in the process.

While this year’s Fellows are busy in Africa, PiAf staff, board members and alumni have been busy reviewing the 464 applications we received for next year’s 45-50 fellowship posts, as well as applications from fantastic new potential partner organizations. We remain amazed at the number of bright, skilled, passionate young adults eager to spend a year of service in Africa – and the inspiring organizations in Africa that are interested in our Fellows’ support.

From everyone here at Princeton in Africa, we wish you a joyful holiday season and a happy new year!

Katie Henneman

Executive Director

PiAf Connections

Please click below to check out pictures of our Fellows, Alums and other members of the PiAf family meeting up at home and around Africa.

Notes from the Field

By Riley Brigham, '13-'14 Fellow with Maru-a-Pula in Botswana

I can’t believe four months has passed since I began working at the Maru-a-Pula School, a private boarding school located in Botswana’s capital, Gaborone. Most days, I catch myself thinking about how I can continue to improve as a teacher, and how much more I have to learn. However, as I walked across campus the other day, I began to realize how familiar my new home has become to me. What was once strange and foreign to me has now become second nature. I chuckle and ask myself, “who am I?” and “where am I?” as I think about the adjustments I have made, and the expressions, names, and positions I have become accustomed to in this new environment.

+ “Ma’am! Ma’am!”

I now instinctively respond to these endless echoing calls. Not to mention adapting the formal title of “Ms. Brigham,” a name that previously only referred to my grandmother.

+ The left side of the road.

Learning to drive on the left side of the road was a very unnerving experience, but now I find myself wondering if I will be able to readjust when I return to the US.

+ Motswana Names.

Learning 90 new names in different languages was a daunting task. Now, “Kgotla” and “Tlotlo” are names that are embedded in my vocabulary.

+ Z = Zed

The letter z has been taken out of my alphabet.

+ Standing.

After sitting in a seat in a classroom for over 17 years, I am suddenly on the opposite side, standing in front of a class of thirty young faces.

+ Pigeon Holes.

As a former British colony, a lot of British lingo has been adapted into Botswana culture. Pigeonholes, cheeky, invigilation, and marking are just some of the new words I have had to learn.

+ “Just now.”

A Southern African expression said to imply they will be arriving or completing a task sometime in the, hopefully, near future. Not to be confused with “now now” or “right now”, whose nuanced applications encompass the flexibility of time in Botswana.

When I arrived at Maru-a-Pula four months ago, I could not have anticipated the new expressions, mannerisms, and people I would encounter. Now, as I find myself adapting to these once unfamiliar aspects of life, I have begun to feel that I am also becoming part of the culture and community of Maru-a-Pula and Botswana. I have had the opportunity to travel to a refugee camp with students and watch as they had their eyes and hearts opened to a community different than their own. I have met student’s parents and developed strategies to help their children. I have watched students struggle, and then eventually comprehend, a difficult math problem.

These types of experiences, the bright and energetic students, and the warm and supportive colleagues are what have transformed the unfamiliar into the familiar. And so, with every “ma’am” I respond to, I realize I have begun to be a part of this community I entered just a few months ago.

Notes from the Field

By Alex Hellmuth, '13-'14 Fellow with Olam International in Ghana

At 6am I am in the car on my way to visit Kabile, a large community outside of Sampa in Ghana’s Brong-Ahafo region. As the Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility Manger with Olam Ghana’s Cotton and Cashew businesses, I am managing projects aimed at improving the livelihoods of smallholder cotton and cashew farmers. In Kabile, the Olam team of cashew buyers and I are training cashew farmers in the best practices for farm sanitation and maintenance. The only time to meet with farmers is early in the morning, before they hop on their bicycles or motorbikes and “go to farm.” I am here to communicate to farmers why we are holding these training sessions, and what they can expect from Olam as a trusted community partner. Before moving to Ghana, I had never set foot on a cotton farm nor did I know cashews grow out of an apple on a tree! Needless to say, the first 3 months here has been filled with an ongoing education from Olam’s staff on how to grow cotton and cashews and how to understand the market for both commodities.

I traveled to Sampa along a very bumpy, dusty road from my more permanent home with the Olam Ghana Cotton team in Tumu—a small town on the border with Burkina Faso. I have become quite well acquainted with Ghana’s roads. In any given week, I travel about 200 km visiting the villages surrounding Tumu to meet with Olam’s contracted cotton farmers. Most of the cotton and cashew farmers speak very limited English, so I am learning how to effectively communicate through a translator—the power of a smile and a handshake cannot be underestimated.

I help to supervise the Farmer Business School program that, in sum, teaches farmers how to manage their income from cotton. For farmers who have never kept a budget, this information is life changing. For Olam, it is beneficial to work with farmers who can pay back pre-season loans. The villages surrounding Tumu bear the marks of short-lived development projects, and I am enjoying witnessing firsthand how a private company can be a vehicle for sustainable development in Africa.

This morning in Kabile, nearly 200 women attended the meeting. It was humbling to listen to the challenges they face as female cashew farmers. I always appreciate the candidness of farmers—even when they ask me, “Miss, what do you know? I have been farming cashew since before you were born.” Well you do have a point….

Later today I will head to another town in Brong-Ahafo before making the long journey back to Tumu. After three months, Tumu is starting to feel more like home thanks to its welcoming residents and my wonderful colleagues. Here’s to hoping the air conditioning works in my car for my next long journey.

Notes from the Field

By Beverley Mbu, '13-'14 Fellow at Save the Children in Ethiopia

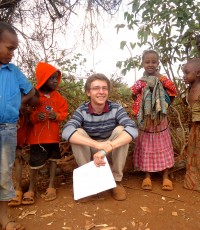

From left: PiAf Fellows David, Elise, Alex, Kristin + friend Sarah & Bev eating at famed cultural restaurant Yod. Abyssinia

Sometimes two months feels like two years, and other times it feels like two minutes since I crawled off my 14 hour flight from DC and landed in the hills of Addis Ababa. Life has been busy from the get go. As the home of the African Union (AU), Addis Ababa is home to people of all nationalities, many migrants from rural areas, more goats than anyone can count, and a charming variety of stray cats and dogs.

In my work at Save the Children’s AU Liaison office I get some insight into Africa’s largest regional mechanism, spending time interacting with a broad variety of international, regional, and national advocates who all share some degree of passion for African development. I have the privilege (and the entertainment value) of seeing how the African Union works up close: it’s intricacies and weird protocols (in case you were curious, the official name of Ethiopia is the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, and woe to you if you do not use this full title in official circles), but also its unprecedented access to the representatives of 54 of Africa’s 55 countries (did you know that Morocco is not a member of the African Union? This is because the AU recognizes Morocco’s disputed neighbor, the Saharan Arab Democratic Republic, and in protest Morocco withdrew from the AU in 1984.)

Aside from a fascinating introduction to African regional bureaucracy, I keep plenty busy outside of the office. I have the pleasure of co-organizing an open mic night of poetry and performance with PiAf Fellow Elise Barry (IRC) at a newly opened reggae bar in Addis. The crowd is warm, the performers are brave, and as host I get to tell, and laugh at, my own terrible jokes. Perfect balance! When not bouncing around on stage, I also tutor English to three Senegalese siblings, who teach me patience and make me laugh more times than I can count.

Addis is busy and thus quite polluted, so any chance I get, I try to focus on two key things: getting out of the city to hike and enjoy Ethiopia’s stunning scenery, and eating. I’m still soliciting visitors, so if you’ve always wanted to come to Ethiopia now is your time!

Notes from the Field

By Dana Nickson, '13-'14 Fellow with Equal Education in South Africa

I have always been captivated by social movements. I saw struggles for change as not only evidence of collective power, but an affirmation of the persistence of love for oneself, others, and future generations. These movements were quite magical in my imaginings. Subsequently, upon hearing that I would work at Equal Education (EE)– a citizen driven movement working towards an equal and quality education system in South Africa through analysis and activism– I was thrilled about the opportunity to merge my love for people and knowledge on the continent.

My daily learning process here often begins with a bus commute from Cape Town’s city center to Khayelitsha, the most populous township in the Cape Town area. The bus is by no means the most efficient route, so there is naturally time to think and a lot to see. The bus meanders through the southern suburbs into Athlone and Mannenberg– primarily Coloured areas; next you hit Gugulethu, Nyanga, Phillipi, and Khayelitsha– primarily black areas. On this bus ride, you see many different Cape Towns: you physically perceive the stubborn remnants of apartheid’s brutal system of displacement of Coloured and black communities; you hear the unparalleled diversity of South Africa’s people; you see the baffling inequality that is so disproportionally divided amongst this diversity. Each time I arrive in Khayelitsha, I have noticed something different during my ride. This bus ride always serves to complement my day; reminding me of what Cape Town’s city center can, at times, allow you to forget.

Upon arriving at EE’s offices, I am always greeted warmly and with jokes by other staff members of the Youth and Community departments. Their jokes are often inspired by my attempts to speak isiXhosa and how quickly my words run out. Once I settle in, it’s easy to feel like there are a thousand things going on. Youth and parents are in and out of the office. An upcoming youth group needs programming and activities to run. School restrooms need to be cleaned as a culmination of sanitation campaigns running in schools. Survey data must be interpreted to share with EE’s high school members known as Equalizers. There is always a meeting to attend that was scheduled to start 20 minutes ago. In between what must be done, there is always time for another laugh or story.

As I have more experiences, I am less inclined to idealize what I can now see is often hard work, yet, I’m steadily learning that these same initial perceptions and the ability to imagine are important in building more equitable and empowered communities in our world. The more I learn about the social dynamics, politics, and histories in South Africa, it is apparent that the commitment of learners, parents, community members and staff is exactly what I admire about social movements. I am honored to be a part of work that signals that new realities are possible and on their way.

Notes from the Field

By Stefanie Siller, '13-'14 Fellow at Mpala Research Centre and Wildlife Foundation in Kenya

My morning routine is very typical: I wake up, brush my teeth, enjoy some breakfast and a very large cup of coffee, and jump in my car to head to work. The rest of my day, however, is rather far from average: my driving route lacks roads, my office has no walls, and my colleagues are, to say the least, anything but usual.

Pop quiz: what is big, grey, and likes to charge at your car when you get too close? If you thought ‘elephants,’ you are correct, and if you thought ‘why in the world would you want to get close enough to make them charge?’ the answer is simple: it’s my job!

At the Mpala Research Centre, I collaborate with the elephant monitoring team to manage the Adopt-an-Elephant program. Whenever an elephant is adopted, the monitoring team collects information on the adopted elephant, and I send out quarterly updates to the adopter. This month, however, I was given the incredible and intimidating task of monitoring the elephants myself.

Despite their immense size, these ‘ninjas of the bush’ can be very difficult to find, and finding the single individual you need amongst hundreds is even harder. Once an elephant family is located, identifying the group is the primary objective. An elephant can be identified based on the distinctive markings on its ears, as well as its tusks. The gender and age of the elephants in the group is also useful in determining which elephant family it is. Indeed, it is actually the other part of elephant monitoring that gets a bit trickier.

There are two main rules for researchers at Mpala when you come across an elephant. 1: do not get too close and 2: do not leave or turn off the car. I break both of these rules daily. In addition to identifying the elephants, I must report on their activities and reaction levels, or, in other words: how close can I get before they charge? Furthermore, it is necessary to take photographs of each elephant in order to keep our database up to date. Both of these tasks require driving as close to the elephant as I can, and then leaving the car in order to obtain the best photograph possible. My biggest lesson of the month: always wear good running shoes!

As amazing as this experience is, what makes it even better is that it is not mine alone. With every update that I write, I am able to bring the excitement and pleasure of working with elephants to the adopter, allowing them to share in the delight of living with wildlife. As the Princeton in Africa fellow at Mpala, this is just one of the ways that I find myself translating the majesty of Mpala to the rest of the world. By connecting this wildlife with viewers and readers, individuals from across the globe can enjoy, learn about, and actively participate in life and conservation at Mpala.

Notes from the Field

By Alex Villec, '13-'14 Fellow at the BOMA Project in Kenya

Five months in Kenya have stretched me well beyond the bounds of my job description. Even though data constitutes the bulk of my monitoring and evaluation (M&E) work with the BOMA Project, the non-quantifiable aspects of life in Nanyuki have left the greatest impression so far. It’s impossible to put a dollar value on the sunrise over Mount Kenya, to predict utility gains from mastering the national dish, or to capture in a statistical model the fulfillment that comes from learning a new language.

While these experiences resist measurement, so too does the complex interaction of economic behavior, social networks, and cultural norms present in communities where we work. The BOMA Project targets the poorest micro-entrepreneurs in pastoral communities where recurrent drought and conflict undermine a deep-seated tradition of livestock herding. With seed capital, training, and two years of mentoring, BOMA aims to “graduate” participants from poverty.

All right, then, what does success look like? Is food security priority number one, or do sustainable incomes and business growth take center stage? Can a household with diversified assets better withstand the dry season, or does a financial investment in a young girl’s education actually tell us more about a household’s resilience in the long-run? Having identified the relevant indicators across these categories, how do we analyze, weigh, and interpret them to tell a story about what’s happening in Kenya’s arid and semi-arid lands? BOMA has afforded me the privilege of chewing on these questions around the clock.

On weekends, however, adventure lurks in the flower- and corn-studded pasture that envelops the rich foothills of Africa’s second highest peak. Nairobi’s cosmopolitan allure trickles up north on occasion, but the rural charm of a bustling and personable market town is Nanyuki’s greatest asset. It’s a place where cashiers at the Budget Grocery Store know you by name, where newspaper sellers stop to chat as you finish off a lunchtime plate of ugali and nyama choma (roasted meat), and where fruit vendors tell you “Haina shida, utanilipa kesho!” if you’re ever short on coins – no worries, you’ll pay me tomorrow, they say.

Working at a small NGO means that each staff member has a seat at the decision-making table. Within days I had thrown myself into two self-directed reporting projects and, within weeks, a wholesale revision of our current approach to savings group data collection. Leadership and management float major program changes from top to bottom, understanding that BOMA will only continue to grow if each team member is personally invested in the work we do. This involvement means getting into the field with program participants, advancing new ideas, and constantly seizing opportunities to move us forward.

Apart from the daily Swahili, crisp mountain air, and unbounded autonomy of driving myself to the office, BOMA’s organizational culture underlies the most liberating aspect of my fellowship to date: If something isn’t being done, it’s because I’m not doing it yet. It’s a culture that empowers and I wouldn’t trade it for the world.

Notes from the Field

By Eliza Warren-Shriner, '13-'14 Fellow at World Food Programme in Senegal

My first three months in Dakar have been full of surprises—new food (both good and bad), new people, and all that comes with transitioning from the bubble of college to a full time job in the “real world.” Working at the World Food Program’s (WFP) West Africa regional bureau has had its own surprises, whether learning the “language” of WFP (what’s the difference between moderate acute and chronic malnutrition? En Français?), or even which language to use (my Portuguese has made little progress).

What has been perhaps most surprising, however, is that the Dakarois, both native and imported, LOVE to work out. Although not quite what I expected to find in a primarily Muslim country, I’ve been pleasantly surprised to find a huge range of ways to “exercise” my athletic juices. I realized, in recent weeks, just how much these experiences have been indicative of my time in Dakar.

+ Running

People in Dakar run. A lot. Our taxi ride to work each morning passes two beaches where several huge packs of Senegalese men run drills together, and runners are everywhere. Running has allowed me to discover the city, whether exploring my neighborhood, watching the city wake up, or engaging with fellow Dakarois. The latter of these experiences has been most powerful; while I have learned to ignore honking taxis (no, I don’t need a ride—I’m running!), or “friends” who try (and often fail) to keep up, running has often afforded the opportunity to engage with Dakar on a personal level. As one of just a few females (and toubabs) seen running, it has helped to build my confidence as I get to know my new home.

+ Frisbee

Dakar is truly an international city. I live with an Italian; work with Canadians, Germans, Ghanaians and Cameroonians; spend time with Congolese, English and French; and run with Senegalese, Ivoirians and Central Africans. While many of my athletic pursuits have been quite international by nature, I found my Frisbee experience—a sport gaining popularity in the US—fascinating. Among the mix? Americans (7-year olds to 70-year olds), a French vet student, and a Senegalese semi-pro basketball player (whom I carefully avoided guarding). Like many experiences in Dakar, the combination somehow worked.

+ Body Attack

Club Olympique (the local gym) has become a second home, and not just because it provides a consistent shower. People are so full of life there; we clap at the end of classes, smile after a third set of push-ups and get pushed by ever-enthusiastic instructors in loud French. While Zumba, BodyCombat, spin and Pilates have been on the agenda, BodyAttack is my new favorite. After jumping, running, lifting and dancing, we complete our last set in the center, gathered around our sweaty, energized instructors, and there’s a sense of camaraderie and joy in a room filled with expats and Senegalese, students and professionals, beginners and seasoned experts…this, for me is Dakar.

Still on the agenda? Judo, badminton, rock climbing, salsa dancing, baobab climbing…really, the possibilities are endless.