January - February 2016

Dear Friends,

Happy 2016! We hope you enjoy reading this month’s edition of the Fellows Flyer, which includes photos taken during our 2016-17 Fellow interviews here in Princeton, and an Alumni Profile written by Allie Stauss, PiAf 2014-15 Fellow with African Cashew Alliance in Ghana, who now works in international development and splits her time between East Africa and the U.S. If you’d like to read more about our nearly 400 other alumni, check out our website’s Fellows Directory!

Warm regards from Princeton,

Jodianna Ringel

Executive Director

PiAf Connections

Please click below to check out pictures of our Fellows, Alums and other members of the PiAf family meeting up at home and around Africa.

Notes from the Field

By Danielle Allyn, 2015-16 Fellow with Gardens for Health International in Rwanda

“Veggie Photos” are a tradition at Gardens for Health, and every GHI team member poses for a shot as a “rite of passage” on the farm.

A Thousand Hills, A Thousand Stories

20th-century African-American novelist James Baldwin wrote in Notes of a Native Son that “I love America more than any other country in this world, and for this reason I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” As a semi-retired college activist and an aspiring human rights lawyer, I’m primed to approach social justice and thus my life’s work operating under the premise that reasoned critique serves as a necessary pillar for progress and change. I still believe this. However, after six months giving voice to the stories of smallholder farm communities and photographing verdant green hills in 2015 Rwanda, I’m beginning to understand that constructive critique can and should take many forms. Angry letters to the editor, defiant protest signs, and controversial social media posts exist as targeted strategies for social change in 2016 America. This does not mean, however, that these are the most appropriate methods for inspiring change in every context. In Rwanda, as I aim to represent the complete stories of Gardens for Health partner families in the Musanze and Gasabo districts – nearly 2,000 families enrolled annually – I’m learning that change can happen quietly. I’m learning that decentralized change can in fact take place in partnership with centralized institutions. I’m learning that speaking the truth does not always mean speaking loudly, and that affirming progress can be just as necessary to transformation as righting wrongs. Here are some other things that I am learning:

+ No matter how conscious I am of my privilege and how much I strive to tell stories that recognize and validate the humanity of GHI partner families, my “outsider” status means I will always have blind spots, and I’m humbled by the role that my Rwandan colleagues continue to play as cultural ambassadors.

+ The story of malnutrition in rural Rwanda is complex and rooted in socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic reality. The solution, however, is simple and adaptable: small-scale, sustainable agriculture and nutritional diversity. In a country with over 75% of men and women engaged in farming, agriculture must be part of any plan for sustainable development.

+ Some stories cannot be fully appreciated absent context. Before living and working in Rwanda, I had no way of knowing that healthcare decentralization and affordable health insurance programs have revolutionized access to care even in remote areas. I could not fully grasp the challenges associated with terraced farming and the way that unpredictable weather – a product of climate change – places the livelihoods of smallholder farm families in jeopardy.

+ Kinyarwanda – buhoro, buhoro (slowly, slowly)

Notes from the Field

By Jessica Chirichetti, 2015-16 Fellow with International Rescue Committee in Tanzania

Jessica (far right) working with a Burundian refugee teacher during a textbook distribution at schools in Nyarugusu Camp.

About eight months ago I was at my desk in a DC office when I received a breaking news alert on my phone: “Burundi slips into political crisis as President seeks third term,” and then a few days later, another news alert, “Tens of thousands of refugees flee into Tanzania.” I called my Dad in a panic and asked, “What am I getting myself into?” I had recently accepted a fellowship position as Program Assistant in IRC Tanzania’s Kasulu office. The IRC is the main agency responding to the refugee crisis in Tanzania and Kasulu is less than one hour’s drive from Burundi.

Since the day I arrived, I have been inspired and humbled by the admirable work of IRC and its partners in responding to the influx of more than 110,000 Burundian refugees in Nyarugusu Camp, making it the third largest refugee camp in the world. I jumped right into the work and soon learned there was never a shortage of things to get done. I was eager to have a hands-on learning experience, and what better way to learn than joining a massive coordinated humanitarian emergency response? My colleagues and I attend emergency Saturday meetings, hold late-night budget sessions, conduct advocacy with media outlets and write countless proposals in hopes of providing the best quality of services to the refugees.

The moment I realized the enormity of the crisis was during the first month of my fellowship. I had a long day of rolling out a new M&E system to track progress in the tent schools in the camp. UNHCR alerted us that two buses of refugees were arriving from the border. Despite the long night of work ahead, we drove to the reception center inside the camp. The sun was setting and a truly picturesque African sky surrounded us. It seemed to me slightly ironic as the situation unraveling was pure chaos. Children were crying and searching for missing parents, people were injured and looking for food. Exhausted families faced intense scrutiny during security searches for weapons. I admit, I froze and my only reaction was to stare. I felt shame that refugees were put through this process and I was worried that the situation will only get worse. On the way back, my colleagues and I were silent, hiding tears behind our sunglasses. And I was right to worry: the crisis in Burundi continues, some say the country is on the brink of another civil war. Three new refugee camps have opened in Tanzania. The emergency response continues.

Despite the emotional rollercoaster of my fellowship, I could not be more thankful for PiAf for this opportunity and my IRC colleagues for pushing me to reach a professional growth that I did not think was possible. I’ve now seen both sides of humanitarian aid, the harsh reality and shocking inequality, but also the truly life-saving impact it can have.

Notes from the Field

By Erin Collins, 2015-16 Fellow with UN World Food Programme in Malawi

Since I arrived in Malawi in August, I have spent a large amount of my time working on our current emergency response that is providing food assistance to 2.4 million people countrywide throughout the current lean season. Seventeen percent of the population here in Malawi is currently food insecure, so it makes sense that this response requires a lot of our time in the office. That being said, during a field visit in October, I discovered more fully my excitement for resilience work as it pertains to development. Rather than just responding to shocks and emergencies, WFP is helping farmers adapt to climate change through innovations that help build resilience to weather shocks.

I saw one such innovation at work when I traveled to the southern district of Balaka for the installation of 15 rain gauges – instruments that record rainfall and help trigger insurance payments to farmers if rainfall is insufficient. A full day was spent installing the 15 rain gauges at the homes of rural farmers. After arriving at each home, we would greet and meet the head farmer and his/her family. Installing the gauges involved cutting down a piece of wood to the correct size, fastening a holder where the beaker would be placed, digging a hole deep enough in the ground to secure the rain gauge, and then once constructed and in place, re-explaining the proper use and maintenance of the rain gauge. I was mostly an observer of this process as my one attempt at helping to dig one of the holes made it very evident that I have little experience in using farming tools. However, I was fortunate enough to have time to speak with the farmers who expressed gratitude and a willingness to work hard and take ownership of this project, as well as feelings of hope for a more successful future harvest.

Putting faces to the beneficiaries of these projects was quite moving. Seeing their homes, families and lives was humbling and really put the level of poverty of so many Malawians into context for me. Overall there was something so wonderfully intimate and personal about the experience. Every family welcomed us in their own way – we were offered fresh mangoes by one woman and were welcomed with song by another. At several villages, huge groups of kids would gather around us out of curiosity for what it was we were doing; meanwhile several times it seemed like the entire village came to be a part of the installations in some way.

We ended our day at a little stand in one of the villages where goat meat was purchased for a small braai. Little did I know that the meat would be cut right off a recently-skinned goat hanging directly in front of us. I will admit, I was a bit skeptical, but I ended up really enjoying it – so much so that we went back for round two the following day.

To read more about Erin’s fellowship experience, you can visit her blog.

Notes from the Field

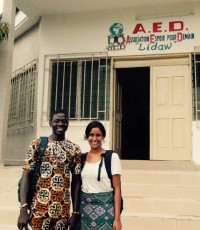

By Monica Dey, 2015-16 Fellow with Hope Through Health in Togo

Monica (right) standing with Chris (the coordinator of Hope Through Health’s pediatric HIV program) in front of the AED/HTH clinic.

Last year, on a sunny March morning at Stanford, I woke up to an e-mail from Princeton in Africa informing me that I had 72 hours to decide whether I wanted to accept a yearlong fellowship for an organization called Hope Through Health in rural, northern Togo. They couldn’t tell me exactly what I would be doing, but it would involve HIV and access to health care.

I panicked. I quickly typed in “Togo” on Google Maps to make sure I knew exactly where that was and called my best friend in distress. How could I leave all of my friends in California to work in one of the most rural PiAf sites, and a French-speaking country at that? My friend calmed me down and told me that I was being ridiculous, that I of course had to accept the position. How could I not work for Hope Through Health? He was right. I took a deep breath and told Princeton in Africa “yes.” Yes to uncertainty, yes to risk, yes to fear.

I would love to say that since coming to Togo, I have made enormous, systemic changes in the care for HIV+ children in local communities. I have not (yet). But I have been learning every day that by accepting uncertainty, I am opening myself up to a world of opportunities I did not know were possible. I have been able to visit pediatric patients in their homes, to shadow medical assistants at the nearby dilapidated hospital, to create a quantitative measure for family engagement, to plan participatory activities for children during Club Espoir support groups, to develop a healthcare delivery strategy and quality improvement plan for pediatric HIV, to run open-ended feedback sessions for staff members, and to become a part of my vivacious work family. As my fellowship progresses, I am hoping the combination of these experiences will transform into tangible, positive changes for our patients.

While saying “yes” to uncertainty has absolutely taught me about the incredible complexities of community-based development in the field, it has also taught me an important, useful life lesson. Uncertainty is not scary on its own: what is scarier is figuring out how I should respond to it. Instead of panicking and turning down something that scares me, I am starting to use “yes” as a life mantra. Working in Togo has taught me to walk directly into the flame, to do my best to address problems I see – no matter how complicated, delicate, or time-intensive – and to do so with a deep sense of humility and gratitude. With the rest of my time in Togo, I hope I can inspire others to do the same: to say “yes” to uncertainty with me.

Notes from the Field

By Anya Lewis-Meeks, 2015-16 Fellow with Maru-a-Pula in Botswana

I have just come back from a month-long vacation at my parents’ home in Providence, Rhode Island as part of the December/January vacation at the Maru-a-Pula School in Gaborone, Botswana. As a teacher, the vacation time I get as a part of my fellowship is crazy – we had a month in August, a month in December/January and will have another in April/May.

Some of the other Botswana Fellows met up in Zanzibar and Cape Town for Christmas; still others spent their time in Northern Botswana and Zimbabwe. I knew that I wouldn’t be able to miss Christmas with my family, but I myself was looking forward to the long break. I dreamt of hot showers and speedy Wi-Fi, of gorging on Chipotle and Starbucks. When I arrived home, I did all that I planned and less, divvying up my free time from writing grad school applications between watching television and doing halfhearted reading.

I returned to Gaborone a week ago, and in that time I’ve been nervous about how I’m going to go adjust to my “hectic” life. So to remind myself why I’m here and what I’m grateful here for, I’ve made a list of five things I have to look forward to in the next six months:

- Teaching curricula I’m familiar with — When I first started at Maru-a-Pula, I knew nothing about the San, the Khoikhoi or the Oorlams. Now I not only can pronounce all those terms, but I’ll at least know way more than the 12-year-olds!

- A whole new set of Form 1s — What can I say, I’m excited for the newbies! While I’ll still be teaching a group of Form 3s I taught last year, I’m excited to be molding the minds of the youth just as they start high school.

- A wedding — A couple of my closest friends are moving to Johannesburg and while I’m very sad about it, at least I get to make up for it by attending a real South African wedding.

- The PiAf retreat — Finally going to make it to East Africa! In all my time spent on the continent (admittedly, not that much) I’ve never made it above Zambia. Well, I’m very excited to explore a new part of the continent, and reconnect with the PiAf Fellows (and staff!)

- Old friends (and new ones!) — Gaborone is an extremely transient place, and people tend to move out almost as soon as they arrive. By being here for a year, I’m actually one of the longer-standing members of the expat community. While many of my friends are leaving the city this year, I’m not letting that bring me down. Most of them are moving to nearby South Africa, which just means new places to visit, and new couches to crash on. And on top of that, new people come in all the time! I can’t wait to welcome others to Gabs the same way I’ve been welcomed here. Bring on the next six months, yebo yes!

Notes from the Field

By David Lunde, 2015-16 Fellow with Kucetekela Foundation in Zambia

David (right) with KF’s Executive Director Florence Nkowane (left) and KF alum Margaret (middle) as Margaret leaves to study medicine in Russia.

It’s Tuesday morning in Lusaka and I’m speeding down an unknown road trying to keep Mr. Mukena in my sights as he zips around cars. The recruitment of KF’s next class of scholars is in full swing, and we’re heading to the next primary school to conduct another group interview. I’ve been in Lusaka two weeks and have no idea where I am, so I press the gas to desperately keep up.

Kucetekela Foundation is an NGO that sponsors high-achieving, vulnerable students from the compounds of Lusaka to attend Grade 8 to 12 at two private boarding schools. To that end, KF initiates a rigorous recruitment to select its next cohort. Engaging in the recruitment was my first and foremost responsibility during my first two months in Zambia. Together with Mr. Mukena, the Finance Manager, and Florence Nkowane, the Executive Director, we interviewed 150 students at 19 primary schools spread across Lusaka. The group interviews were a great chance to see how the students express themselves and hear how they think. One question I often asked was “If you do improve your community in one way, what would you do?” I remember well one student, Lazarus, whom we ended up sponsoring, telling us everyone has to fetch water from the community well, so he wants to build pipes to every home. During the interviews, we found out about the students’ backgrounds, academic interests, and outside activities. The interviews were also a great way to explore different areas of Lusaka and orient myself to the city. Seeing the schools and speaking with guidance teachers and head teachers taught me about challenges in the state of education in Zambia.

After the interviews, we collect applications with information about the students’ academic and extracurricular performance and socioeconomic background. We use a rubric that ranks the students based on academic potential and level of vulnerability. Many Zambian students drop out after Grade 7 because families can’t afford the increased Grade 8 boarding fees. So we try to identify intelligent students facing that situation.

After scoring the applications, we narrow down to 50 students and invite them to sit an exam in English, math, and science. The top 15 students advance to the penultimate round, where we conduct interviews with the students’ families in their homes. It’s a sobering reminder of the conditions most Zambians live in, as no families had running water and half didn’t have electricity. But it’s also a reminder why KF exists, because we believe in the power of quality education to ultimately improve these families’ situations.

We select our 10 best students and propose them to the board of trustees. In December, we received the news that our fundraising team in the US raised funds to sponsor all 10 students! When I returned in January, I was excited to welcome our new students to the family. I look forward to spending the next six months with them as they begin to develop into the next generation of Zambian leaders.

Notes from the Field

By Kelsey Miller, 2015-16 Fellow with International Rescue Committee - Somalia (based in Kenya)

One of the most important things I’ve learned during my fellowship year is how important it is to have activities and a routine to look forward to outside of work, particularly when living abroad. These activities have helped me to acclimate to life in Nairobi by keeping me from getting stuck in a routine revolving only around my work and my apartment, and they’ve introduced me to a lot of interesting people from across the city.

So, after work on Mondays I go to a great yoga class by the Africa Yoga Project, Tuesdays we have a Nairobi Fellows group dinner, and Wednesdays I go to an Afrobeat dance/workout class. I was introduced to the Afrobeat dance class by a friend/2014-15 PiAf Fellow, who is friends with the instructor, and I quickly became friends with the instructor in my own right.

Beyond teaching these Afrobeat workout classes around town, the instructor had also been signed to a show called Slimpossible that airs every Friday on Citizen TV – Kenya’s biggest national station. Slimpossible is effectively the Kenyan version of The Biggest Loser; overweight contestants try to lose weight with the support of fitness instructors and nutrition counselors. The contestant who loses the fewest kilograms in a week is eliminated, and the winner of the show wins 1 million Kenyan shillings in a very exciting Grand Finale episode. My friend, the Afrobeat instructor, was commissioned to lead a dance at the beginning of each episode to set the tone for the rest of the show.

Near the end of the season, following the elimination of several contestants, the producers of Slimpossible noticed that the stage was looking a bit empty and could benefit from guest dancers. The Afrobeat instructor invited a few people from her normal Wednesday workout class to appear as dancers on the show for the first few minutes of choreography, before the show gets down to the nitty gritty of determining who would stay and continue competing and who would be eliminated.

And I was one of the guest dancers! The show was so fun and quite the whirlwind – we learned the choreography the night before the Friday show, which airs live, nationally, to a couple million viewers. We had such a blast and were invited back to perform for the Grand Finale episode, which in addition to airing live to a TV audience, was filmed at an invitation-only, live audience, red carpet event!

My big break into the reality TV world in Kenya (on a weight loss show, no less!) has been hilarious, providing great entertainment to my friends back home and my Kenyan colleagues in the office who held mini watch parties, tuning in for both episodes. Needless to say, I’ll be sad to eventually return to the US and give up the celebrity life in Kenya!

Notes from the Field

By Kara Poppe, 2015-16 Fellow with Nyumbani Village in Kenya

Christmas in Iowa is usually filled with joyful holiday programs, stressful last-minute gift runs, and elaborately decorated Christmas trees. This year, Christmas in Nyumbani Village certainly did not include any of those elements, but it was simple and pleasant in its own way. Nyumbani Village is an eco-village that cares for 1,000 orphans infected or affected by HIV in rural Kenya. During the December holidays, the children have the opportunity to go to their homelands and visit their relatives and neighbors for a few weeks. About 200 of the children stay with us during the holidays, because they have no one to take them or the situation at their relative’s home is unfavorable. For these children, it can be an especially emotional time and serve as a reminder of their traumatic pasts. With a limited budget and some help from the surrounding communities, Nyumbani does its best to give the children a nice Christmas celebration.

The week before Christmas, we received numerous visits from local businesses and other children’s homes. Although they had little to share, they all came bringing bountiful donations of staple ingredients, like maize flour, salt, and sugar. It redefined my thoughts on how much I can give living on a modest stipend. Then, on Christmas Eve, the children gathered to decorate our Social Hall for the special Christmas masses. With just some simple ribbons, cloths, and a tree branch, they created wall decorations, a nativity scene, and even a Christmas tree. Another volunteer and I made some basic holiday crafts out of scrap paper, crayons, and bottle caps to brighten up our common room. The following morning, I awoke to the sounds of community members slaughtering a bull outside of my house. It certainly was different from the familiar carols of Christmas morning, but it meant a meal with beef, a very rare treat, was coming. After Christmas morning mass, the children and their caretakers received a portion of beef to prepare and a sack of wheat flour. They spent their afternoon preparing a simple feast of beef stew and chapatis (similar to tortillas). People were together and laughter could be heard throughout the village. There was no visit from Santa Claus, matching holiday tableware, or fancy presents to open, but instead just enjoying a special meal and each other’s company. This year, I have learned that it does not take much for the holidays to be special. The memories from this simple Christmas season in Nyumbani Village, starkly different from the more commercialized (and complicated!) holiday that I am used to, will remain with me for the rest of my life.

Notes from the Field

By Emma Sakson, 2015-16 Fellow with Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation in Tanzania in Tanzania

Emma (far left) and fellow PiAf 2015-16 CCBRT Fellow Kelsie Wilhelm (second from the left) celebrating the publication of CCBRT’s Annual Report with colleagues at an event hosted for former President Jakaya Kikwete.

What’s the last story you read? On what platform did you read it? The manner in which stories are told has changed significantly over the last few years, as the internet has become the most common way many people access news and media. Folks don’t read information anymore; they “consume” it. Articles need to be “digestible,” as if stories are snacks. To reach an audience and communicate effectively, you must adapt to these new rules of digital storytelling.

Everything needs to be shorter. Pithy. But also engaging. Nuanced. Mobile friendly. And shareable across all platforms, please and thank you.

Throughout my fellowship, I’ve been trying to reconcile these new rules of storytelling through my work on the Communications team at Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation in Tanzania (CCBRT). CCBRT is the largest local provider of disability services in the country. In Dar es Salaam, CCBRT operates a Disability Hospital that treats patients for a range of orthopedic and ophthalmological conditions, from clubfoot to cataract to obstetric fistula. All care is provided either free of charge or at a highly subsidized rate to ensure that everyone has access to high-quality healthcare, regardless of their ability to pay. CCBRT also runs a rehabilitation center in Moshi, hosts outreach clinics in rural areas, and strengthens Dar’s existing maternal healthcare system through a capacity-building program that works in 23 partner facilities across the city.

There is a lot going on at CCBRT.

So how do I tell all of these stories in a way that is nuanced and engrossing, but also concise and cohesive? Attempting to answer this question has been a large aspect of my experience at CCBRT, and in the process, I have become more cognizant of how my race, gender, privilege, and age shape my ability to tell these stories.

I don’t have many answers, but I’ve learned a lot from asking the questions. In keeping with the new rules of digital media, below is a list of the most salient things I’ve learned from my fellowship thus far, in 140 characters or less.

+ Don’t count your chickens until they hatch. Once they do, count them twice & build an impenetrable fence around them. Then count them again.

+ Words matter. Language matters. Take the time to get the words and language right.

+ It takes more time to unlearn something than it does to learn something. It’s important to do both.

+ Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

+ Hashtags may look silly, but they are an effective tool for reaching new audiences. #maternalhealth #fistulainatibika #Tanzania

+ Street food will not make you sick. The fancy restaurant down the street will.

+ Asking for help is not a sign of weakness; it’s quite the opposite.

+ Whether you like it or not, you are an unofficial spokesperson for your country. Try to be an honest, gracious, and open one.

+ Life is too short to say no to chapati.

Notes from the Field

Alumni Profile: Allison Stauss, PiAf 2014-15 Fellow with African Cashew Alliance in Ghana

Allie (left) interviewing a factory worker at Mim Cashew during her PiAf fellowship with African Cashew Alliance in Ghana.

Allie Stauss (PiAf 2014-15 Fellow with African Cashew Alliance in Ghana) graduated from American University with a degree in International Relations. Prior to her fellowship, Allie committed her academic and professional pursuits to the exploration of the African continent, securing Africa-focused internships at the USDA, UNICEF, and the Wilson Center and serving as an agricultural trainer in rural Tanzania. As a Fellow with the African Cashew Alliance, she supported the mobilization of cashew projects in 14 countries through proposal development, technical review of programmatic documents, creation of promotional materials and donor reports, and knowledge management. She also used the opportunity to travel throughout West Africa, engage with her community, and empower vulnerable youth to create art as a tool for community peace-building. After her fellowship, Allie joined the East Africa division of TechnoServe and contributes to the management of its coffee agronomy and sustainability portfolio, splitting her time between DC, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, and South Sudan.