|

August 1 John Arndt

August 3 Luwam Berhane

August 28 Ettie Philitas |

|

Fellows’ Flyer |

|

August 2009 |

|

News and views for and by Princeton in Africa Fellows |

|

In this Issue: |

|

Highlights from 2009-2010 Fellows John Arndt in Uganda and Beza Tesfaye in Kenya and 2008-2009 Fellow Audrey Banks in Sierra Leone |

|

Happy Birthday |

|

You’re Invited to...

Princeton in Africa’s Annual Benefit October 1, 2009

New York City

The Princeton in Africa Medal will be presented to Thomas C. Barry, CEO and founder of Zephyr Management

A special Princeton in Africa Lifetime Achievement Award will be presented to Julius Coles *66, retiring president of Africare for a lifetime of service to Africa

Click here to purchase tickets or for more information

We hope you will join us! |

|

“The guns are silent now.” This is how my supervisor at Invisible Children described the situation in northern Uganda as we sipped warm Cokes. Living in Gulu, you would never know that just a few years ago this place was a warzone. According to some development workers here, four years ago you would rarely even see a car in town, unless it had “U.N.” emblazoned on the side. The chances of seeing a mzungu (foreigner) were rare unless they were in the backseat of the UN vehicle. Now, there is a bit of congestion around 5 PM as people leave their places of business to return home for the evening. I even have the luxury of writing this in a café with an internet connection. Despite being the epicenter of Africa’s longest ongoing war, a land and people ravaged by the warlord Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) of kidnapped child soldiers, Northern Uganda is very much alive and growing right now. The children of Gulu used to have to leave their families and villages every evening to meet in the relative safety of the town center to avoid being kidnapped by the LRA. It seems now you can’t go anywhere in Gulu without tripping over children in brightly colored uniforms coming to and from school. Perhaps most unexpected and inspiring of all, it seems the Acholi are always smiling.

Invisible Children is a unique and young organization, tracing its roots back to 2003 when three amateur filmmakers stumbled into northern Uganda to tell the largely ignored story of Joseph Kony’s child soldiers. Our focus is on improving access to quality secondary education as well as economic initiatives to support the local communities. My role in all this is to help develop a system (or more likely a series of systems) to monitor and evaluate the impact that Invisible Children’s investments are having on the beneficiaries. Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is a must for most large NGOs that report to huge donors or governments, and I have had the challenge of being the first and only M&E officer at Invisible Children. To fulfill this position I have had not only to study M&E theory and practice, but also to decipher the organization’s structure, goals, and capabilities. For the first few months of my fellowship, I will be working with Invisible Children’s “Schools 4 Schools” program, helping in a variety of capacities from reviewing financial ledgers to designing and analyzing surveys that study the impact of our programs. One of the best parts of this position is any chance to visit the schools and speak with educators, administrators, and students.

In an effort to spend even more time at the schools, as well as work off the very starchy and dense Acholi cuisine, I have begun coaching the boy’s rugby team at St. Joseph’s College Layibi, a secondary school. This is no doubt the best part of my day as I get to spend a few hours running around with an incredible group of kids who have never touched a rugby ball before but learn very quickly. I have been invited to join the Gulu Rugby Union which is aiming to establish rugby programs at many of the local secondary schools. We are short on funding (read: absolutely no money) but we do have a group of dedicated rugby fanatics who have a burning desire to see the North become a respected force in Ugandan rugby. In fact, it is that sentiment that drives a lot of things up here: the desire to show what Gulu, the Acholi, and northern Uganda are capable of.

Did my supervisor mean to imply that the guns may not be silent forever? Everyone I meet seems remarkably optimistic that, despite previous periods of stability, now it is for real. Joseph Kony will not come back to northern Uganda. But who knows what the future will bring? I think the message here is that we do not have any time to waste. Northern Uganda had over two decades stolen from it and the time and lives can never be replaced. All we can do now is get to work. |

|

by John Arndt, ‘09-’10 Fellow at Invisible Children in Uganda |

|

Notes from the Field |

|

John, prior to his departure for Uganda |

|

Schoolchildren walk by the Invisible Children office |

|

PiAf alumni gathered on August 3rd in Central Park for a SummerStage concert by American banjo player Béla Fleck and Malian kora player Toumani Diabaté. Following the concert, the group watched Fleck’s flick Throw Down Your Heart, which chronicles his journey exploring different types of music in Tanzania, Uganda, Mali, and The Gambia. |

|

One of the schools that Invisible Children’s “Schools 4 Schools” program is working to improve |

|

NYC Alumni Event |

|

Stay tuned for future alumni events in your area... We hope to arrange gatherings in Boston, NYC, DC, and elsewhere this fall! |

|

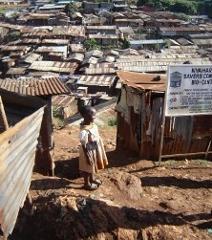

Driving from central Nairobi, the cosmopolitan hub of East Africa, to Huruma, one of the largest slums in the surrounding area, is like a journey back in time. It is only a 10-kilometer drive but the scenery progressively deteriorates from high-rise buildings to the less flashy two-story shops of the bustling Somali neighborhood Eastleigh to the corrugated tin collage that is Huruma; from smooth, paved roads to an array of potholes that only a skilled driver can zigzag through and avoid serious damage to his car.

My supervisor thought it would be a good idea for me to see the other side of Nairobi and to look into ways that the International Rescue Committee (IRC) could engage with urban slum dwellers (many of whom are unregistered urban refugees) through a public-private initiative. After my first two and a half weeks spent reading and reviewing grant reports/proposals, I was more than eager to have this assignment and to witness Nairobi’s notorious slums. So I was off to Huruma to meet and speak with a community organizer who helped found a local NGO known as the Reality Tested Youth Project. This organization started from a modest three-room building donated by the French Embassy and has developed into perhaps the most reputable and resourceful organization in Huruma and Mathare (a neighboring slum).

The key to RTYP’s success in Huruma is mobilization and coordination. For about 500 Ksh a year, RTYP offers membership to community-based organizations. Currently, over 150 CBOs have registered with RTYP and receive valuable support including educational and vocational training, connections with other NGOs and community groups, and access to grants and funds that RTYP has available from donors—in a word, RTYP provides people with the basic skills and resources to pull themselves out of poverty and sustain themselves financially over the long run.

“We don’t like to be told we’re poor; we’re not poor. There are many opportunities here, what we need is coordination,” said the community organizer who showed me around. Hearing these words struck me with a new perspective. Humanitarian work seemed to revolve around the idea that there are those in desperate need and it is our obligation to help them. But I began to question if the way in which NGOs and donor governments interact with communities such as Huruma really accomplishes the goals of development. Reinforcing the idea that people are needy and lack development, by providing them an occasional handout of humanitarian relief, is ultimately meaningless in terms of economic empowerment and sustainability. Fortunately, IRC is one of the NGOs which emphasize community ownership of projects and capacity building as key aspects of program implementation.

I heard profound stories from my colleague who had been working in Huruma since 2004. Stories about women seeking shelter from sexual abuse by Ethiopian OLF rebels; eleven and twelve year-olds who work as child-laborers in the many shops and butcheries and who have never left the neighborhood, let alone seen downtown Nairobi; porters who usually come to the community center to take a shower once a week and have some porridge. But there were also hopeful stories— people starting enterprises, such as an urban farming scheme to sell fresh vegetables in the slums, a garbage collection initiative sustained by contributions made by community members, and cultural dance groups that have performed in places as far away as South Africa. These latter are the stories that are often left out when describing places like Huruma. Yet, what struck me the most about this experience is how people who have very little are able to make ends meet by being a little innovative and working diligently. Most importantly, one realizes that even in these conditions people live life with dignity. |

|

by Beza Tesfaye, ‘09-’10 Fellow at International Rescue Committee in Kenya |

|

Notes from the Field |

|

Beza pours coffee at Habesha, an Ethiopian restaurant in Nairobi |

|

Huruma slums outside Nairobi |

|

Nairobi |

|

With a maternal mortality rate of 2,000 deaths per 100,000 live births, an under-five mortality rate of 270 per 1,000 live births and just 27.5% of the female population literate, Sierra Leone currently occupies the bottom spot on the UN Human Development index for a third consecutive year.

The figures are shocking—indeed, nothing short of an emergency—and yet after writing a string of proposals and editing reports for the International Rescue Committee’s programs in Sierra Leone, there have been times this year when I regarded statements like these as little more than commonplace, if catchy, prefaces to my work. Too quickly, I had grown as accustomed to these statistics as I had to the implacable sounds of hip-hop that spilled out of the open air night club across from my home in Freetown six nights a week (seven if you count the relatively muted Celine Dion Sunday nights).

Initially, I panicked and agonized about having deteriorated from idealistic Princeton in Africa Fellow into jaded aid worker in just a few short months. As I settled into my work, however, I began to wonder if the staggering statistics I regularly exploited sounded flat because I had grown indifferent or rather because the problems they signified seemed too vast and the resources too few for the numbers to really mean anything. Registering the gravity of their implications brings into question whether we are doing enough, if we are doing it the right way and, ultimately, whether the work we do is worthwhile at all.

As Sierra Leone moves away from the post-conflict phase and into development, IRC and other aid organizations have begun shifting their focus from direct service provision towards working alongside the government, strengthening its capacity to deliver quality public services including maternal and child healthcare, primary and secondary education, and access to justice. At the same time, in a country where statistics, particularly health indicators, are more reflective of an emergency than of a development context, the support that some NGOs provide remains critical and the production of quality proposals and reports can be essential to securing life-saving funding.

My work in IRC’s grants unit mainly comprised proposal development, overseeing compliance with donor regulations and ensuring that the reports to donors were accurate and reflected the achievements of a given program. As such, when a project was well designed and its implementation was on track, it was tremendously satisfying to work with the program’s staff to highlight the impact they had made. Given the number of ill-conceived projects that are rolled out in the developing world at any given point, I feel fortunate that the majority of IRC’s current programs are reasonably ambitious, aligned with the Government of Sierra Leone’s priorities, and are having a measurable impact on beneficiary populations. However, if a program failed to achieve its projected targets and I was responsible for packaging the outputs of a reporting period as positively as possible while remaining honest, I questioned my added value—not so much to my organization as to the rather incongruously competitive industry of humanitarian aid and development.

This experience, coupled with a year of fascinating discussions with friends working in government ministries, at UN agencies, other NGOs, and the private sector in Sierra Leone, has offered me a glimpse of the myriad challenges involved in implementing development programs in a country like Sierra Leone: corrupt customs officials that refuse to release life-saving drugs from the port; a debilitating lack of infrastructure that bars partners from fulfilling their roles and beneficiaries from accessing services; inadequate budgetary allocations for public services, leading to unpaid teachers and health workers who resort to charging fees for essential services that should be free; the lack of coordination between aid agencies; and donors who fail to disburse the funds as promised, paralyzing the roll out of projects. Like the sheer scale of the problems reflected in the Human Development Index, these challenges have often felt insurmountable.

But Sierra Leone beats with life. Akon and life. The country is both vibrant and stable. It held one of the few free and fair elections on the continent in recent history; the land is rich with potential to produce rice, cocoa, and palm oil; and Sierra Leoneans are “trying small” to develop their country as evidenced by the slogans—including my favorite “NO FOOD FOR LAZY MAN”—emblazoned across Freetown’s ubiquitous poda-podas (mini-buses).

As I conclude my time in Sierra Leone, I’ll carry the refrain “try small” with me. It is easy to feel as though nothing we do will be enough or that the way in which the world has structured its response will do little to change the situations in Sierra Leone and many of the world’s other poorest countries. Yet, I continue to believe that there is value in working within a system to understand what kinds of questions to ask, who sets agendas and priorities, what makes strong programs and good donors, and to start thinking about how we can all do better.

|

|

by Audrey Banks, ‘08-’09 Fellow at International Rescue Committee in Sierra Leone |

|

Notes from the Field |

|

Audrey in Freetown |

|

The former Hollywood Cinema neighbors IRC’s Kono District office. Kono was devastated during Sierra Leone’s decade-long civil war as government and rebel forces fought for control of the district’s diamond fields. Today, many families reside in the shells of these damaged structures, as they lack the resources to restore or rebuild homes. |

|

Junior Secondary School students in Kenema District. IRC's NoVo Foundation funded Legacy Initiative works to increase quality of and access to junior secondary education, with a particular focus on educating girls. |

|

A young boy heads to work in the diamond-rich region of Tongo Fields in Sierra Leone’s Kenema District. Since 2005, IRC has been implementing a US Department of Labor funded program to withdraw or prevent over 14,000 children from engaging in exploitative labor and enrolling them in schools. |