|

|

|

PiAf Fellow Katie Camille Friedman, at the International Institute for Water & Environmental Engineering (2iE), has entered the Global Social Venture Competition with two current 2iE students from Chad. The three submitted a business plan for an enterprise whose mission is to make more modern, sustainable, ecological and economical homes accessible to the Chadian population. Katie Camille represented her team (called Beti Halali) in Paris and London and will be attending the Global Finals on April 7 and 8 in Berkeley. We congratulate Beti Halali for making it this far and wish them good luck at the finals! For more information on their project and their business plan, watch their YouTube video. |

|

Fellows’ Flyer |

|

March/April 2011 |

|

News and views for and by Princeton in Africa Fellows |

|

As I left a recent meeting at Mwandi Community School (a part of my fellowship responsibilities with African Impact, a voluntourism organization where I serve as a project coordinator), I paused outside the office door. Mwandi sits where the land swells above its surroundings, west of town and skirting the edge of the national park. The sky is wide open, and I could see the billowing mist from Victoria Falls in the distance. My first visit to Mwandi had been over six months before. I had been at work for maybe two or three weeks; I was barely more informed than a volunteer. I drove some of the schoolchildren and the headmistress, someone I’d never met, back to Mwandi after an event. The kids sang the whole way. As I drove down Kazungula Road toward the setting sun, I was in awe. I felt so exhilarated – by the foreign language, by the children’s enthusiasm, by the sunset, by the open sky, by the Falls. As I stood on Mwandi’s porch months later, I realized that the thrilling new has become the comfortable familiar. I’ve now been out there countless times. I had just left a productive meeting with the headmistress; she’s no longer a stranger but a reliable partner. But the view is different, and not just because the spray from the Falls has grown larger. Mwandi has not changed, but my perspective has.I don’t just see the openness and a landmark’s distant mist. I see Nakatindi, another school where I’ve spent hours unloading bricks, reading to children, teaching physical education. I see the area where I spent an afternoon bagging dirt for a garden. I see the road that connects town to the Botswana border. I see the spray from the Falls, sure, but now I think – hey, the river is up, I wonder if it’s getting too high to go rafting? That means it’s fishing season soon… Our meeting was an attempt to start 2011 on the right foot. We reviewed what we’d done at Mwandi in the past and discussed the effectiveness of our volunteers and their projects. The sports program needed more structure, they said. We agreed to follow the national curriculum more closely in our PE courses. We honed the plan for our reading clubs, following their suggestion of focusing on a handful of kids who need the most help. We toured their unfinished ablution blocks and discussed the possibility of helping them complete it. I wouldn’t have even known how to begin that meeting seven months ago; I had no clue how to balance our philosophy and capabilities with the community’s needs and ideas. In the same way that my perspective on the landscape changed, so has my perspective on the projects. I used to see the empty landscape – simply the structure and what the volunteers were meant to do – and now I see the history, the context, the personal details. I can remember what has happened in the past; I can critically examine the projects; I can populate that empty landscape with thoughts and ideas. I’m no longer giddy with excitement at all the newness, but now I get waves of a different, more fulfilling feeling of satisfaction that I’m learning, helping, and, instead of being a tourist, really living here. |

|

Notes from the Field |

|

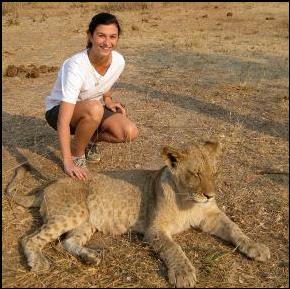

Mary Reid during a lion walk with African Impact’s partner organization, Lion Encounter |

|

Notes from the Field |

|

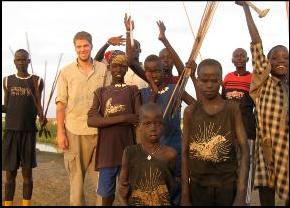

LWF Burundi community members greet LWF staff in the field |

|

Tony on Christmas with his substitute family members |

|

Mary Reid dancing with "Sweet Potato" at a Christmas party for the Maramba Old People's Home |

|

by Tony Speare, ‘10-’11 Fellow at Lutheran World Federation , Burundi |

|

Tel: 609.258.7215 Fax: 609.964.1818 piaf@princeton.edu |

|

Mailing address: Post Office Box 226, Princeton, NJ 08542 Street address: 194 Nassau Street, Suite 219, Princeton, NJ 08542 |

|

Internationally speaking,

Burundi tends to fly under the radar. As the international aid

community continues to pour money into Burundi's closely related

neighbor Rwanda and set up offices in Kigali, funding for NGOs working

in Cankuzo, Burundi's poorest province, is drying up. In terms of

progress towards achieving the UN's Millennium Development Goals (MDGs),

Burundi lags far behind other East African |

|

Blog of the Month |

|

PiAf Africa Travel: Cordelia and Stephanie Visit Fellows |

|

PiAf Alum Emily Holland Publishes Book |

|

On February 1, 2011, the Southern Sudan Referendum Commission, the body tasked with the job of organizing South Sudan’s logistically challenging referendum for independence from the North, announced 3,851,994 of the 3,947,676 Southern Sudanese registered voters (97.57%) cast their ballot. In the historic vote held from January 9-16, an overwhelming 98.83% of these voters, many of which trekked dozens of miles across inhospitable terrain to reach a polling center, chose secession over unity. Unprecedented, this turnout and result astounded people working on the referendum who had not seen such overwhelming percentages in a free and fair election. A history of broken promises and marginalization, first by British colonialists and then by the Arab-dominated Khartoum central government, bred discontent that ignited the Southern Sudanese rebellion. Except for brief lulls and an unstable peace from 1972-1983, fighting last for nearly half a century starting on the eve of Sudan’s independence in 1955 and continuing until the North and South signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005, which provided for the referendum for independence in January 2011. The war in Africa’s largest nation killed two million Southern Sudanese and another four million. Many people, myself included, believed logistical constraints, political intransigence, and minimal education as a result of decades of conflict possibly would delay the referendum, if not make it impossible. South Sudan, soon to become the world’s newest nation once it declares independence on July 9, 2011, though defied the odds. Now with the referendum behind it, the nascent nation, to be named the Republic of South Sudan, faces the immense challenge of building governing institutions and infrastructure, providing basic services, and ensuring security in an increasingly volatile region. Working with IRC Southern Sudan, I have had the incredibly fortunate opportunity to witness the implementation of the CPA, preparation for the referendum, and post-referendum proceedings. Based in Juba, South Sudan’s capital, much of my job consists of days sitting behind a computer at a desk, but work in Juba allows me to relish trips to monitor programs in the remote and destitute, yet stunningly beautiful and always exciting, field sites. Life in Juba though is never dull. A plethora of activities keep me busy and allow me to transcend communities in Juba. An NGO and UN town, Juba is filled with a very unique mixture of people from all over the world uniting to organize the referendum, provide humanitarian assistance, and create a new independent entity from scratch. Each individual I have met has a fascinating story. Countless Sudanese walked for months to escape the war, sought education abroad, and returned to build this nation while expatriates here have worked all over the world in areas people generally only read about in the news. Whether coordinating relief responses for flood victims, drafting healthcare indicators used in facilities countrywide, putting together budgets and proposals, hanging out with friends, or chatting with my colleagues, I continually learn and value my experience in this unique, and often very challenging, environment. I am thankful for the opportunity to be here during such a historic era for not only Sudan, but also the entire continent. With any luck, South Sudan will continue to defy the odds, complete its transformation, and become one of Africa’s greatest success stories, and I eagerly look forward to learning more from those around me and witnessing the next chapter in South Sudan’s history as it prepares for independence!

|

|

Case In the swamps of Ganyliel, Unity State, with Nuer cattle herders |

|

The Countdown Clock in Juba before the referendum |

|

The only thing I had in mind when I applied for the Princeton in Africa fellowship was: “I want to be in AFRICA!” Almost halfway through my fellowship, I realize that I couldn’t have come any closer to that wish, with a slight twist - Africa has been brought to me! I like to think that I am the luckiest of all the fellows as I get to meet and interact with people from over 32 African countries on a daily basis. The African Leadership Academy is indeed a microcosm of Africa. ALA is indeed a paragon of true diversity. Diversity in itself is nothing if not celebrated. It then becomes a mixture of differences. At ALA, the whole community revels in and celebrates its diversity. I remember last year, the founders of the Academy, staff members and students alike fasted during Ramadan. I could not afford to miss out and therefore joined them in the last 5 days of fasting. Joining my Muslim and non-Muslim students and colleagues at the Mosque on Eid was one of the most peaceful and spiritual experiences I have ever had (Coming from an agnostic, this speaks volumes!). Working at ALA has been a real treat. I started off as an Admissions Officer but at ALA one never gets enough of the amazing students. They actually are real stars. If they are not being interviewed by CNN, they are on BBC radio and getting quoted by the likes of Bono (True story!). In addition to recruiting, I now also coach the soccer team, teach Cambridge A-level French literature, and play surrogate father to a group of 6 advisees. I like calling Kenza, Tom, Mariem, Steve, Lebogang and Sophie “my kids” and they [sometimes] call me the “best adviser ever.” I usually take them off campus to the mall or to hang out at my place. Exploring Johannesburg is absolutely essential for their education. Otherwise, they would not know that traffic lights are called “robots” and that it’s completely OK for roads to change names as you drive along them in South Africa. Imagine how confused they would be when given directions to my place: Turn left on Juice [Street], then make a right at the robot [when it is green of course!]. Turn left on Northumberland, I mean, Witkoppen. At the fourth robot, turn right. Now, the robot may or may not work since it usually does not work on 4 out of 10 days. They also need to know that avo is short for avocado, else there will be too much ado about avo [especially when reading restaurant menus]! Avo is used in/on everything! Avo on pizza, Avo in salad, Avo in mayonnaise (Ok, I made that one up but seriously, it can happen here!) I still need to introduce them to Haloumi cheese which has to be fried before eating (yes you heard properly, you have to FRY the cheese! But it tastes delicious!) All in all, they need to know that Johannesburg gets more flack than it deserves.

|

|

by Veda Sunassee ‘10-’11 Princeton Class of ‘72 Fellow at African Leadership Academy, South Africa |

|

Notes From The Field |

|

Veda shares lunch with some of his advisees and gets updates on their studies and their lives |

|

Veda coaching the ALA soccer team, who somehow manage to laugh and joke around despite their rigorous training exercises |

|

Highlights from 2010-2011 Fellows: Case Martin in South Sudan, Mary Reid Munford in Zambia, Tony Speare in Burundi, Veda Sunassee in South Africa and Joe Vellone in Senegal. |

|

by Case Martin, ‘10-’11 Fellow at International Rescue Committee, South Sudan |

|

Notes from the Field |

|

Stephanie and Fellows Christina Jung (Baylor/Bristol-Myers Squibb Children’s Center, Lesotho), Allie Gips (mothers2mothers, South Africa) and Hannah Burnett (m2m, South Africa) in Maseru, Lesotho. |

|

Emily Holland, ‘01-’02 PiAf Fellow with the International Rescue Committee in Rwanda, is the co-author of AND STILL PEACE DID NOT COME: A Memoir of Reconciliation, about the former child soldiers of Liberia and a woman who became their champion.

The Liberian Civil War (1989-1996 and 1999-2003) was one of the bloodiest in Africa’s history—Liberia is recovering from its harrowing past, trying to heal the wounds of a scarred country.

As part of the healing process, the Liberian government is encouraging those involved in the war—both victims and perpetrators—to come forward and tell their stories, acknowledge the past, and vow to move forward. Emily worked with Agnes Kamara-Umunna, a native Liberian now living in Staten Island, New York, who is a foot soldier for this cause, coaxing former child soldiers to share their tragic histories in order to free themselves and help their country move on. AND STILL PEACE DID NOT COME is Agnes’s emotional story of war, and finding peace among the ruins. On March 30 a book launch event was held at the Princeton Club of Northern California including George Hritz, President of PiAf’s board, and Rory Eakin,‘02-’03 Fellow at UCT Quantitative Literacy Project.

|

|

My Fellowship by the numbers 1. The number of other Princeton in Africa fellows in Dakar. I am spending my fellowship year working at the UN World Food Programme with Molly Slotznick ’10, though we are working in different departments: I in program design, and Molly in communications. Molly and I are by far the youngest people working in the office, which highlights what an incredible opportunity our PiAf fellowships have given us. My day-to-day job involves designing new food assistance projects in the 19 countries our bureau covers. Often, these projects are proposed by the WFP offices in the host country and reworked by my department, but sometimes we are actually charged with designing a program from scratch, meaning we get to go on mission to the country (see number 3 below). 2. Average number of hours of electricity that I have at my house each day. Senegal is enduring what has been called the worst electricity outage in 15 years. These daily power cuts have fueled social unrest in Dakar, and popular protests have become commonplace. As social unrest spreads throughout the region, talk has turned to Senegal becoming the next Tunisia. Indeed, just as in Tunisia before the revolution began in earnest, a man burned himself alive in front of the presidential palace in Dakar last month. 3. The number of missions I have been sent on for my job at WFP. I’ve traveled to Cameroon, Mauritania, and Mali to assist WFP staff there in formulating upcoming programs, from feeding refugees to piloting a local-purchase program that supports smallholder farmers. 4. The number of minutes it takes me to get to the beach from my house. I live in a 4-bedroom house with three other young UN professionals: a Swede working for UNHCR, a French working for UNODC, and a Swede also working at WFP with me. Just across the street from us is a small dirt path that leads down to a magnificent beach, with dramatic cliffs, white sand, and a little hut selling Coke, beer, and crepes. 5. Minimum number of cheers I receive during my evening runs. Fitness is a strong component of Senegalese male culture, and is tied to the tradition of lutte, a form of wrestling that holds a place as the national sport of Senegal. As a result, Dakar’s streets and beaches become flooded with young men each evening before sundown, preparing themselves for their next lutte. But this custom is not limited to the Senegalese, and toubabs (foreigners) such as myself are often greeted with cheers and high-fives as we run alongside the locals and participate in this evening ritual. 6. The number of talibé left to beg on my street corner. Talibé are, at least nominally, young boys who are sent by their families to live with a marabout (a religious leader belonging to the Sufi Muslim brotherhood) in order to pursue a free religious education. However, in Senegal, many marabout have taken advantage of this tradition to exploit the children: the parents of talibés are typically very poor and unable to provide paid education for their children, and in exchange for his education a talibé must beg on the street for money that goes to the marabout. While this longstanding practice can be stopped through political pressure from the government and civil society organizations, unfortunately there is little one can do to help, which often leaves me feeling powerless and despaired. However, buying food and water for a talibé at least ensures that they are well-nourished, and I always keep a few bananas in my bag for the boys – no older than 8 – who live just down, and literally on, the street. |

|

Cordelia enjoyed dinner at Carnivore in Nairobi, Kenya with Fellows Chris Courtin (Nyumbani, Kenya), Helaina Stein (Generation Rwanda, Rwanda), Victoria Shepard (IRC, Kenya), Allie Bream (WFP, Ethiopia), Tony Speare (LWF, Burundi) and Theresa Laverty (Mpala, Kenya). |

|

Cordelia with Fellows Katie Fackler (WFP, Benin), Katie Camille Friedman (2iE, Burkina Faso), Elly Sukup (WFP, Ghana), Becca Balis (IRC, Liberia), PiAf alum Oliver Barry and his fiancé Christian Lynch in Ghana. |

|

Stephanie taking in the scenery in Camps Bay with mothers2mothers Fellows Hannah Burnett and Allie Gips, and PiAf alum Byron Austin and Iming Lin, both currently living in Cape Town. |

|

During their Africa travels, Cordelia and Stephanie met with many prospective partners, some of which are now official new PiAf partner organizations. A lot of potential exists for future fellowship years as well. Our new 2011-12 partner organizations are:

African Cashew Alliance Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village The BOMA Fund eleQtra Equal Education Greater Good Olam International Project Mercy Save the Children Student Sponsorship Fund Ubuntu Africa

|

|

Update: New ‘11-’12 Partner Orgs |

|

News from the PiAf Office: —Update: New 2011-12 Partner Organizations —PiAf Fellow Katie Camille Friedman in Social Venture Competition |

|

Digging the car out of the ubiquitous rainy season mud on the way to deliver much needed medicine to a remote community in Northern Bahr el Ghazal |

|

Current Fellow Molly Slotznick (World Food Programme, Senegal) recently wrote a piece for the WFP’s internal website about the PiAf fellowship program. Her article can be viewed here. |

|

by Joe Vellone ‘10-’11 Fellow at World Food Programme, Senegal |

|

Notes From The Field |

|

This beautiful beach is just a few minutes from Joe’s house in Dakar |

|

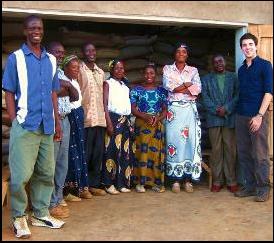

Joe met with the management committee of a WFP-supported grain bank in Cameroon |

|

PiAf Fellow In Social Venture Competition |

|

WFP Article |

|

Name of blog: Intersections Written by: Becca Balis, 2010-2011 Fellow at IRC Liberia

From a recent post: “…Thoughts from the field: In a region notorious for its violence, horrific civil wars, villainous warlords and child soldiers, the deteriorating situation in Cote d’Ivoire appears to only confirm stereotypes of war-torn Africa. However, I’m living on the other side of the border and am seeing different stories in Liberia.

Yesterday I went to some of the locations where refugees are currently living in Nimba County. I’m still completely astounded by the generosity that I saw in host communities. Liberians in small, rural towns are literally sharing their homes with refugee families. Most rural Liberians’ homes are already relatively crowded and have very minimal supplies, if any. Still, as would be expected in West Africa where the concept of ‘too crowded’ does not exist, families are simply making space. They are doing in this in schools, health facilities, farms, and community structures as well.

Additionally, many host community members fled to Cote d’Ivoire during the Liberian civil war. I spoke with one woman who had lived with an Ivoirian family for six years and now is hosting a family of four in her home. She showed me that although war seems to be the most obvious linkage between Liberia and Cote d’Ivoire, the reality is that generosity is the stronger bond between these two resilient nations. She is demonstrating the fantastic generosity familiar to those of us fortunate enough to live in Africa. It is this quality that challenges the images of war-torn Africa with a different stereotype of the continent – that of welcoming, open people with big smiles and always with room to spare.

Although my optimism is driving me to share these positive stories, I felt such overwhelming helplessness walking through the transit center. I watched 17 Ivoirians, some with infants, exit the back of a truck where they’d been crammed for a six-hour drive on horrendous roads. There is such a sense of despair – many of these people fled their homes in the middle of the night after hearing gunshots for days...”

Read more of Becca’s blog here! |

|

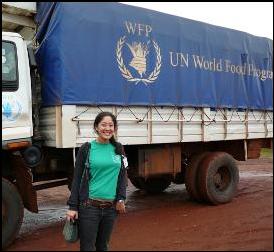

by Molly Slotznick ‘10-’11 Fellow at World Food Programme, Senegal |

|

World Food Programme Article |

|

“Princeton Fellows: From Ivory Tower to the Field” “Molly, you have to be very careful next year. Africa is a very dangerous place… By the way, where is Senegal again?” So went the guidance I received from a former high school teacher just weeks after graduating from university and weeks before leaving for my first trip to Sub-Saharan Africa for a year-long position at the WFP regional bureau in Dakar. I heard many similarly vague pieces of advice in the months before my departure as I told people about my upcoming year. Even my mother bought me 85 SPF-strength sunscreen to protect against what must be the hot African sun (to be fair, I burn easily). I don’t mention these anecdotes to reveal the misconceptions of friends and family. I can’t blame anyone for making generalizations about an entire continent when it is a place that is little known to most Americans — except, of course, from the periodic headlines or evening news stories on ethnic violence, political corruption and chronic poverty. Indeed, it might have been several more years before my own knowledge of this vast continent extended past that gained from university courses and academic research. However, I was fortunate enough to receive a fellowship through Princeton in Africa, or PiAf, a non-profit organization that places recent college graduates in one-year posts all over Africa. Launched in 1999 by a group of Princeton alumni, faculty and staff as an independent affiliate of Princeton University, PiAf aims to promote a spirit of service for its fellows by matching them with organizations that work in such varied fields as humanitarian aid, public health, education, conservation, post-conflict reconstruction, and social entrepreneurship. More than 200 fellows have worked in 30 countries and with 40 organizations in the intervening years; 19 of them have worked with WFP in nine African countries, including five in the current “class” of fellows. Each fellow brings a particular strength or experience to their posting with WFP, in my case an academic background in public policy, climate change and development. In exchange, we spend a year gaining a rich life and work experience that for many of us ignites our career path. At least one PiAf fellow has gone on to employment at WFP: Samuel Clendon, now a consultant in the Yemen country office. I arrived in Dakar fresh after graduating from Princeton University to work in public information in the regional bureau in July 2010. I work with country offices to enhance local, regional and global awareness of WFP's activities in West Africa, including media visits, press releases, web stories, promotional videos, newsletters and other visibility material. For example, I recently traveled to Burkina Faso to film a segment of a video that was later presented by the regional director to the Executive Board. The other fellows at WFP include Joseph Vellone (Dakar regional bureau), Allie Bream (Ethiopia), Katie Fackler (Benin/Togo) and Elly Sukup (Ghana). Joseph, in the regional bureau’s programme support unit, works with country offices to formulate and revise upcoming food assistance programmes. Allie, who works in Addis Ababa in public information, has developed the WFP Ethiopia Newsletter, implemented a youth outreach programme at a local international school, and is now writing and designing the country's annual report. Katie, the pipeline and reports officer in the Benin/Togo country office, manages the pipeline, drafts communications materials and major reports. Elly, serving as a programme officer, manages the food for work and food for training programmes as part of Ghana's Protracted Relief and Recovery Operation (PRRO). WFP contributes to our housing and living allowance, while PiAf provides us with health insurance and a “command center” back in Princeton, New Jersey that helps guide us through the challenges that inevitably arise from living in the developing world, far from our families, friends and familiar cultures. For many of us, this is this first time we’ve embarked on such a grand adventure. Fortunately for me, and also because I am in the big and bustling (and also modern and safe) city of Dakar, I will have many happy stories to bring home with me to combat the recurrent TV images of killing and desperation. Of course, I see ethnic violence as the regional bureau prepares to act in response to tensions building in Guinea; I see corruption; I see poverty on the sidewalks in front of the mosque across the street from my apartment as they are filled each night by those who have nowhere else to go. But I also see generosity, kindness, and hope in my daily life. Rama, who runs the canteen in our office, has a laugh that echoes throughout the building as she pokes fun at those whose French is not up to her standards. Daouda, my landlord, bought a sheep to celebrate the Muslim holiday of Tabaski—then gave all of the meat to the poor people who sleep in front of the mosque. Antoinette, my housekeeper, travels several hours each day to and from the city in order to make enough of a living to send her children to school. And on a recent trip to Burkina Faso, I met a man named Ouagadougou (yes, like the capital) who is now able to provide regular food, health care, and education to his family due to the new market access he gained through WFP’s Purchase for Progress initiative. I know that when I return to the United States next summer, I will have at least accomplished the task of literally putting Senegal on the map for many back home. In addition, I hope that I can paint a picture of Africa, or at least my little corner of it, that is not quite so dark and scary as some people might imagine. |

|

The garden in the courtyard of Joe’s house often makes him forget he’s living in the Sahel |

|

Molly with children who are accompanying their parents as they harvest corn in the fields outside Dedougou, Burkina Faso |

|

PiAf alum Lindsay Locks (WFP Uganda 07-08) |

|

PiAf alum Callie Lefevre (WFP Senegal 09-10) |

|

PiAf alum Adrienne Clermont (WFP Benin 09-10) |

|

by Mary Reid Munford, ‘10-’11 Fellow at African Impact, Zambia |