|

Fellows’ Flyer |

|

January/February 2009 |

|

News and views for and by Princeton in Africa Fellows |

|

nyc Alumni Gathering

PiAf alumni gathered in New York on January 13th at Executive Director Cordelia Persen’s home. The group sipped South African wine and shared stories. Pictured below are Marilyn Michelow (07-08), Alyson Zureick (07-08), Alexis Okeowo (06-07), Cherice Landers (06-07), Board member Schuyler Heuer, Page Dykstra (06-07), Justin Barton (03-04), and Nike Lawrence (08-09).

Stay tuned for future events in your area! |

|

In this Issue: |

|

Happy Birthday |

|

January 4 Katherine Anderson Kevin Block Joe Falit

January 6 Lindsey Stephens

January 12 Sam Clendon

January 15 Liza Hillenbrand |

|

Sam models “traditional” office attire in Mauritania |

|

by Sam Clendon, ‘08-’09 Fellow at UN World Food Program in Mauritania |

|

Notes from the Field |

|

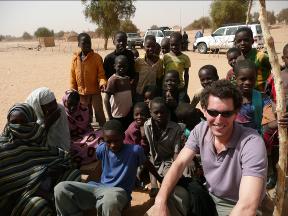

Les gamins (kids) in Gorgol Province |

|

Below: an overheated convoy in the Sahara |

|

I am not one to believe in superstition, but by any measure my introduction to Nouakchott appeared inauspicious. The French Embassy in New Zealand took its time before denying my application for a Mauritanian entry visa, stating that I was a security risk and potential over-stayer. Personal authorization from the Mauritanian Minister of Foreign Affairs was put in jeopardy when, on August 6th (less than a week before my arrival), the military staged a coup d’état and promptly put the aforesaid minister under house arrest. The check-in desk in Cape Town refused point-blank that Mauritania was a country, let alone that Nouakchott, a dusty desert city of more than one million people, could be its capital. They appeared very eager to send my luggage to Mauritius, which did not strike me as such a bad idea, palm tree-lined beaches suddenly replacing images of camels and dunes in my head. And after sixteen hours of hell locked in the tiny floodlit security room that is Dakar airport’s idea of ‘international transit,’ watching an eternal replay of the Women’s 10,000-meter race—sadly the only part of the Olympics that I saw—I approached with some trepidation the last leg of my journey to the République Islamique de Mauritanie. Fortunately such sentiments were unfounded...

Although I know it’s a time-travelled cliché, flying across the Sahara Desert is still a breathtakingly stunning experience. Mauritania’s 500-mile coastline of white sandy beaches and rolling Atlantic waves runs unbroken from Senegal in the south to Western Sahara in the north. Inland, the desert becomes a sea of ever-changing reds and yellows stretching beyond the horizon. I am told that there are thirteen different colors of sand in Mauritania… and I fully intend to see all of them, insha’allah. Dune waves are broken by rocky plateaus and palm oases, but the first thing that strikes you about the country is its vast and beautiful emptiness. Weekend explorations require 4x4s, GPS, and convoys in case one vehicle gets trapped in the swiftly moving sand, yet have offered the most satisfying rewards of my six months in Mauritania: the burning days and cooler desert nights; the clearest skies I have ever seen; the aggressive hospitality of nomadic pastoralists and their endless cups of sweet tea served beneath a khaima; dune-surfing and bronzing on empty beaches.

The overwhelming openness of the Sahara contrasts with the urban chaos of Nouakchott. Most guidebooks are remarkably accurate when they note that “Nouakchott is a hot, sprawling, and unremarkable city of sand-coloured buildings, which merge seamlessly with the encroaching desert.” Sandy pistes outnumber paved roads; donkey-driven chariots transport water and jostle with beaten-up Peugeots and ancient Mercedes taxis; men uniformly wear blue or white boubous billowing around them; sewerage disposal is simply a large hole dug in the street in front of your house, sprinkled with lime and left to the oppressive heat and wandering families of goats to digest. Water is scarce (as I write this, our cistern is empty and the national water utility refuses to reconnect us until we pay our exorbitantly inflated bill), and alcohol or bacon even more so. I continue to fight an ever-losing battle against the sand that is an omnipresent part of life here, forever finding it in my clothes, bed, and food.

Yet Nouakchott is a fascinating city. Sitting on my terrace as the sun sets and the air cools, I am always impressed as millions of bats flood the sky and herald the stars. The central mosques’ daily calls to prayer still wake me at 5:30, before the stillness of the city quickly lulls me back to sleep. Watching the colorful boats arriving at dusk at the ‘Port au Peche’ brings fresh fish, while exploring the city’s lively markets one can find both contraband jamon smuggled in from Spain and cold beers from China (both a massive ‘no-no’ in this strictly Islamic country, and thus luxuries or little victories to savor). My house was an actual—and is now a literal—‘auberge Mauritanian’ and veritable tower of Babel, while Mauritania’s diplomatic recognition of Israel has led to violent protests over the past month with my house (well-positioned in the heart of the city) being tear-gassed by riot police on several occasions… always something interesting to write home about.

My work with the World Food Program (Programme Alimentaire Mondiale) is just as stimulating. The vagueness of my official title (Management Support) has given me the freedom to develop my own projects while working in conjunction with the country directors “to ameliorate the vision and strategy of the country office.” Thus my job has taken me from working with malnourished children along Mauritania’s southern river border, to ateliers on the beaches of central Senegal. For the coming six months I intend to maximize all opportunities that my fellowship and my office offers me: the projects that I am developing encompass every development actor from government agencies and microfinance institutions to local NGOs and other UN agencies – in other words, a crash course in the practical implementation of international humanitarian programs. On both a personal and professional level, Mauritania is far from an easy country, and yet continues to surprise at every turn. |

|

I can only imagine how disheartening it would be to live in a place where, if it were hypothetically enfranchised in some weird twist of fate, the bovine community would hold a popular majority in all local elections. But such is the reality of Magude, Mozambique, a small town two hours northwest of Maputo. Life is simple there, in Magude, and for better or worse there isn’t much for the locals or myself to do. It has probably been a cow town for a very long time. Recently, however—and by recently I mean sometime since 1970, or maybe earlier—it also became a sugar town. Down the road and across the long train bridge, sugarcane fields spread out as far as the eye can see, distinguished by towering mechanical watering arms that slowly sweep across the lush African landscape. The cane is processed in a massive factory that runs 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, regardless of weather or holidays or the personal feelings of anyone in particular. If I had to hazard a guess, I’d say that this factory employs close to 70% of Magude’s working population and is the only explanation for this town’s continued existence. Workers in blue jumpsuits--men and women, old and young--are driven to the fields and home again in overgrown yellow cages by roaring green tractors. And so this is Magude: cows and sugar, the ancient and the modern. I guess, in the end, and on either side, it is still a cattle town.

In a very small way, I’m trying to change that. I work and live in Maputo as the Program Manger in Education for the Lurdes Mutola Foundation, a small, do-it-all organization that focuses on improving the lives of Mozambican youth, particularly women. One of my responsibilities is to manage a program based in Magude called Mais Escola Para Mim. This program selects girls from the most rural areas of the Maputo Province and boards them in a dormitory complex near the Magude Secondary School. These are farm girls that would not otherwise be able to continue studying because of poverty, isolation, and traditional expectations of early marriage. Sometimes they are the first in their villages, let alone families, to make it beyond primary school. All meals and school fees are provided, along with uniforms, books, and the care of two social workers. In the dormitory setting, these girls prove to be quick learners. By stressing the value of education, sorority, and personal empowerment, the Foundation tries to nurture their modest dreams.

I recently returned from a five-day trip to Magude. It was a somewhat representative weekend, if also significantly less distracted. The excitement that the girls usually provide was not available to help me pass the time; they were all on summer vacation. I was there as a sort of foreman, making sure a construction team was working productively on the two new dormitory houses that the Foundation is building. It’s not my normal position and I filled it somewhat awkwardly, as I have no experience in masonry and did not know how to judge or direct their craftsmanship. Plus, I was the youngest in the group and was the only one who wasn’t a husband or a father. If I made any impact it was because I was white and there. We got along fine, though, myself and the workers. Perfectly amiable. I played soccer with them and afterwards treated the group to two rounds of beer at a baraca. Just a little token, I thought, something that would both confirm my manhood and show a little appreciation for their toil under the hot sun.

Later that night, I found myself sitting alone with another drink at the makeshift counter, talking in Portuguese to an older Mozambican fellow who controlled the ice chest and crates of beer. Eventually I revealed to the bartender that I was American and not Brazilian or Spanish, which is normally the first assumption, and at this he paused and said something that at the time, perhaps because of my lubricated state of mind, seemed profound. He said, “You know what I like about Americans? Even when they don’t understand my country, they still find a way to make the best of it.” This made sense to me. This felt about right. There is so much about Mozambique and development that I still do not understand and there are days in which I feel utterly lost, but I’ve nevertheless valued my time here and I’m proud to say that I’ve learned a great deal. The fellowship has been, more than anything else, an education in humility. There have been trying periods, for sure, but none so heavy as to outweigh those powerful and concentrated moments that every so often catch me by surprise, and change my life. |

|

By Kevin Block, ‘08-’09 Fellow at Lurdes Mutola Foundation in Mozambique |

|

Notes from the Field |

|

Kevin on the waterfront in Mozambique |

|

Maputo skyline |

|

Kevin (far right) celebrated the holidays in Zanzibar with new Tanzanian friends and PiAf Fellows Tim Callahan, Katherine Anderson, Stuart Campo, Emily Stehr, and Nana Boakye |

|

January 25 Jessie Cronan

February 9 Sarah Hammitt

February 21 Tim Callahan

February 25 Amity Weiss |

|

Coming Up: 2008-2009 Fellows’ Retreat

· Training leaders · Exploring issues affecting the African continent · Sharing best practices · Networking · Developing post-fellowship careers and lives of service |

|

Other News…

We received a strong batch of applications for our 2009-2010 fellowships. Thanks to all PiAf alumni and Board members who assisted with candidate interviews in January! We look forward to sharing the details of our newest class of Fellows with you as soon as the placement process has concluded.

Congratulations to 08-09 Fellows Stephanie Keene and Carl Owens for being co-winners of the Ruth Simmons Thesis Prize! Stephanie and Carl and their work were highlighted in the spring newsletter of Princeton’s Center for African American Studies. |

|

February 5-9 Nelspruit, South Africa |

|

Sam with children who benefit from one of WFP’s 637 supplementary feeding centers |

|

A traditional Mauritanian rural family with the baby and child eating WFP supplementary nutrition rations (that are also being enjoyed by the goat!) |